Zoya Taylor

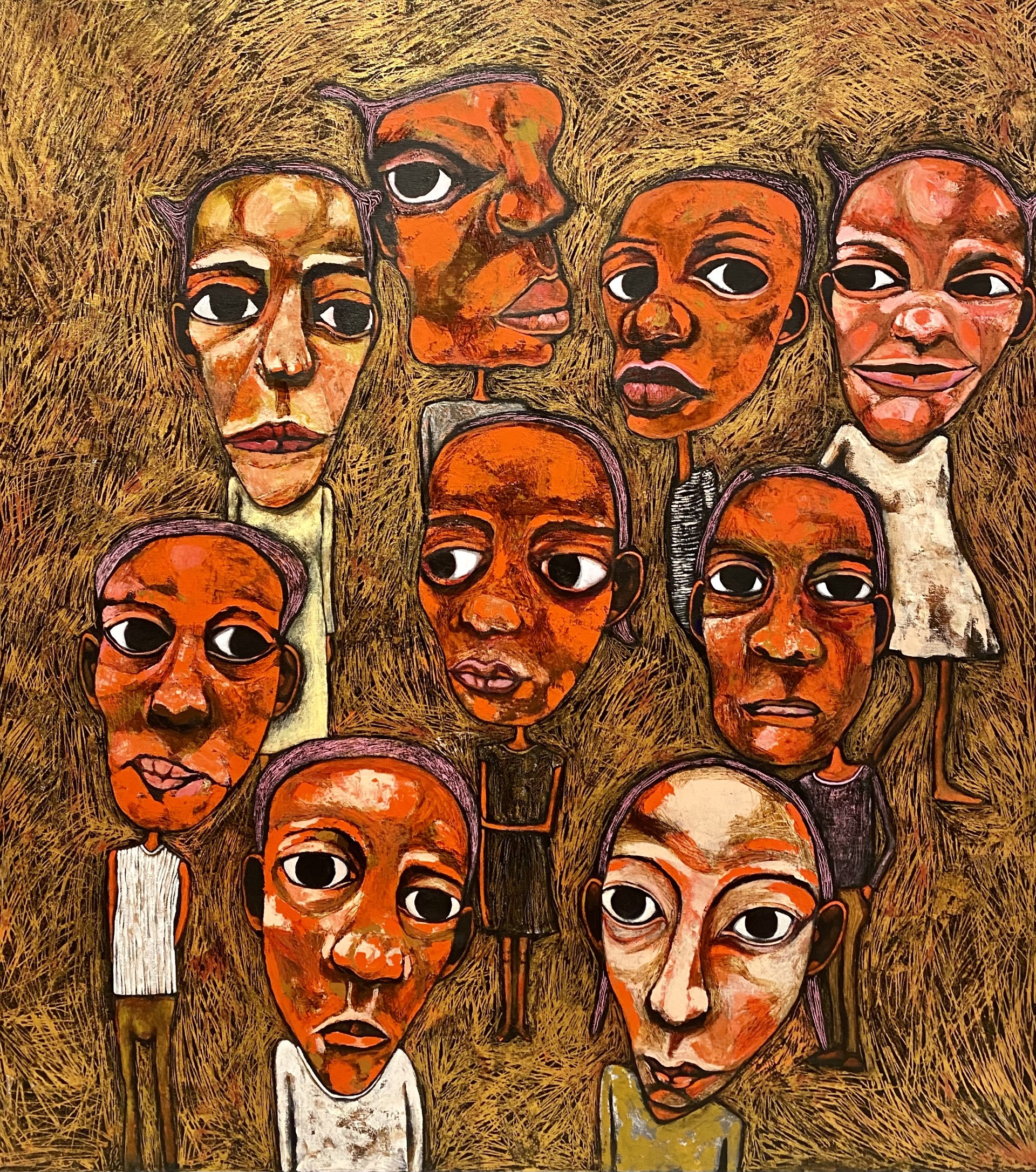

Zoya has a characteristic style of expressionism that is so completely uniquely her own, at first glimpse there is an element reminiscent of Modigliani, her paintings hint at a similar defiance. She captivates a distinct character, not only as a surrealist gesture that may be unintentional, but it’s that innuendo of the parody that holds the attention in the big-eyed characters she paints. Her paintings may reveal the idea of a portrait, the bold colours and patterns illuminating her diverse background and influences. At the same time, the quirky theme of individualism, with her enigmatic caricatures, that radiate an energy evocative of Kehinde Wiley’s colourful vibrancy, in a contemporary African-American theme, and sometimes combined with charged and disquieting narrative, skirting avant-garde movements. It’s the influences of the Intuitives, a Jamaican artistic style, that embodies an idea of attunement to self, the conscious and or unconscious knowing, in expressing things as how they see them, that resonates with Zoya. The Intuitive artists, coined by Dr. David Boxer in 1979, an artist and scholar, at the time director and curator of the National Gallery of Jamaica, are distinct at being self-taught. They were often categorised alongside Western folk artists and are unique to Jamaica’s artistic heritage.

When I meet Zoya she lives in Oslo with her family, having spent a large part of her adult life in Norway. Her mother is Canadian and her father is from Jamaica, and Zoya was born in Vancouver. However she spent the early years in Germany as her father was a lecturer, and his Canadian transfer system had him teach Chemistry abroad, in Freiburg, close to the French border. Zoya spent two years at the French school, and she remembers drawing all the time, and her parents taking her to art galleries as they travelled regularly, and she recalls the impact of a Henri Rousseau painting of the Sleeping Gypsy and the impact it had on her. “We were quite privileged in art and music, my parents were old-school academic hippies” Zoya explains. When Zoya was eight years old, her mother decided that they should move to Jamaica, Zoya describes their journey in a banana boat in 1968, docking at night, and the dark black of the sky, the heavy heat of the air, and this strange feeling of coming home. She loved the wildness, intense smells and entering into a world of colour in contrast to her life in Europe. Zoya spent the next 10 years in Jamaica, even when her parent divorced. She was inspired by the political scene of the 70s, the evolution of Black Power, and the anti-colonial rebellion.

Zoya tells me about the art gallery in Kingston, in the building where her mother worked. It was the first branch of The National Gallery in Jamaica. Her mother was a social researcher for the Institute of Jamaica, and Zoya spent hours in the library, she described the artwork in the museum, It was the art of the time, the Intuitives, that Zoya paid attention to. This is where the art had its grassroots, it stepped away from the more traditional artists. However, she still had the influences of European art she had visited with her parents, and artists like Alberto Giacometti and Egon Schiele still had an impact on Zoya. Her British education in Jamaica took her to her O-levels, and in the late 70’s her mother and sibling moved to Canada. Zoya describes how she was into the Rastafarian scene and was at odds with high school, and when at 17 she moved to Ontario with her mother, at the time, she disliked the city intensely and returned to Jamaica two months later. However, when her mother moved to British Colombia on the West Coast, Zoya followed and attended University, to study sociology, community development and Social Work.

“The idea of service was ingrained at an early age,” she tells me, yet she was painting all the time. “I guess in some way I knew I was always meant to paint. I have always drawn and painted”. Zoya emphasises her fear of being an artist at first. Her idea of being grounded and responsible seemed more important, describing her conservatism and choice of career, as a response to what she describes as her “crazy parents”. She knew she would have to support herself, so she decided to study sociology, as an artist she was seeking stability. “The wish of being an artist was always there. I suppose everybody does something in their life that can be considered art,” she tells me. She continued her education with a Bachelor’s in Community Development and a Master’s in Canada in Social administration. She was travelling extensively, spending six months backpacking South America and Europe. It was in Montreal, whilst working in child assault prevention, working with the black community and teaching at McGill University part-time, that she decided to move back to Kingston, Jamaica with her Norwegian partner. She describes the great job she had teaching in Jamaica, however all through this time she continued painting. Zoya emphasised that it was for herself, and she was regularly visiting galleries in Jamaica, and she started collecting art. Eventually, her husband wanted to return to Norway, and they settled in Oslo, where her children were born. She was hired at nine months pregnant with a teaching position, and Zoya describes to me the remarkable childcare facilities in Norway, with a daycare centre on campus, and six months of no teaching, paid, for both parents. However, she split from her husband a short time later.

It was when she married her second husband, that the opportunity to paint, full-time was possible. They have been together now for over 20 years, Zoya tells me. “I have always made images and expressed myself visually, but it took me some time to develop the conscious intention of becoming a painter and to come to the recognition that I had to paint” she explains. We start to talk about her unique painting style, and how it evolved, “I was scared to because it requires total honesty, a loss of control to some degree, and a great deal of criticism both from within and without” she describes her earlier work as being more representative, describing it as looking more outwards than inwards. Her paintings reflect all the bits and pieces of her life coming together.

As a self-taught artist, she recalls some drawing classes as a child, however being a late starter, “I wanted to finally devote myself full-time to the work itself” she explains, and most of the artists she knew were all self-taught “I didn’t want to attend art school at that stage of my life.” We talk about what or who inspires her art “Memories, everything, life I could have lived, dreams, childhood and all the fairytales, films and books”. As a collector herself, Zoya belongs to a photography foundation. I ask her about her favourite artists, and she mentions the Intuitives like Milton George and Roy Reed, plus contemporary artists like Wangechi Mutu, I can see she has a long list, so I stop her. We talk about whether narrative is important, “Art can be seen as a form of service . My narrative isn’t central. Your response your interpretation is” Zoya explains. “To the extent that visual art is a form of storytelling and I think that I share my own personal narrative of otherness. An otherness both in relation to family and in relation to my experiences of living in different cultures.” Then I questioned her about her ambitions, “I hope to be as truthful as I can in terms of what I do” She continues “What I make. And to continue to struggle and then experience the magic moments of ease. The feeling like everything has meaning if only for a fleeting moment.” What she considers perfection, “The relationship between the imaginary and the real”

Spence Gallery has recently completed a solo show at VOLTA featuring most of the pieces presented in this article. Spence Gallery will again do a presentation of her work at Atlanta Art Fair from October 3-6 2024.

Interview: Antoinette Haselhorst

©️ C-A-K-E Contemporary Art Keen Enthusiast Ltd. All rights reserved.

Excerpts permitted with credit and direct link. Full reproduction prohibited.