Antonio Lopez Reche

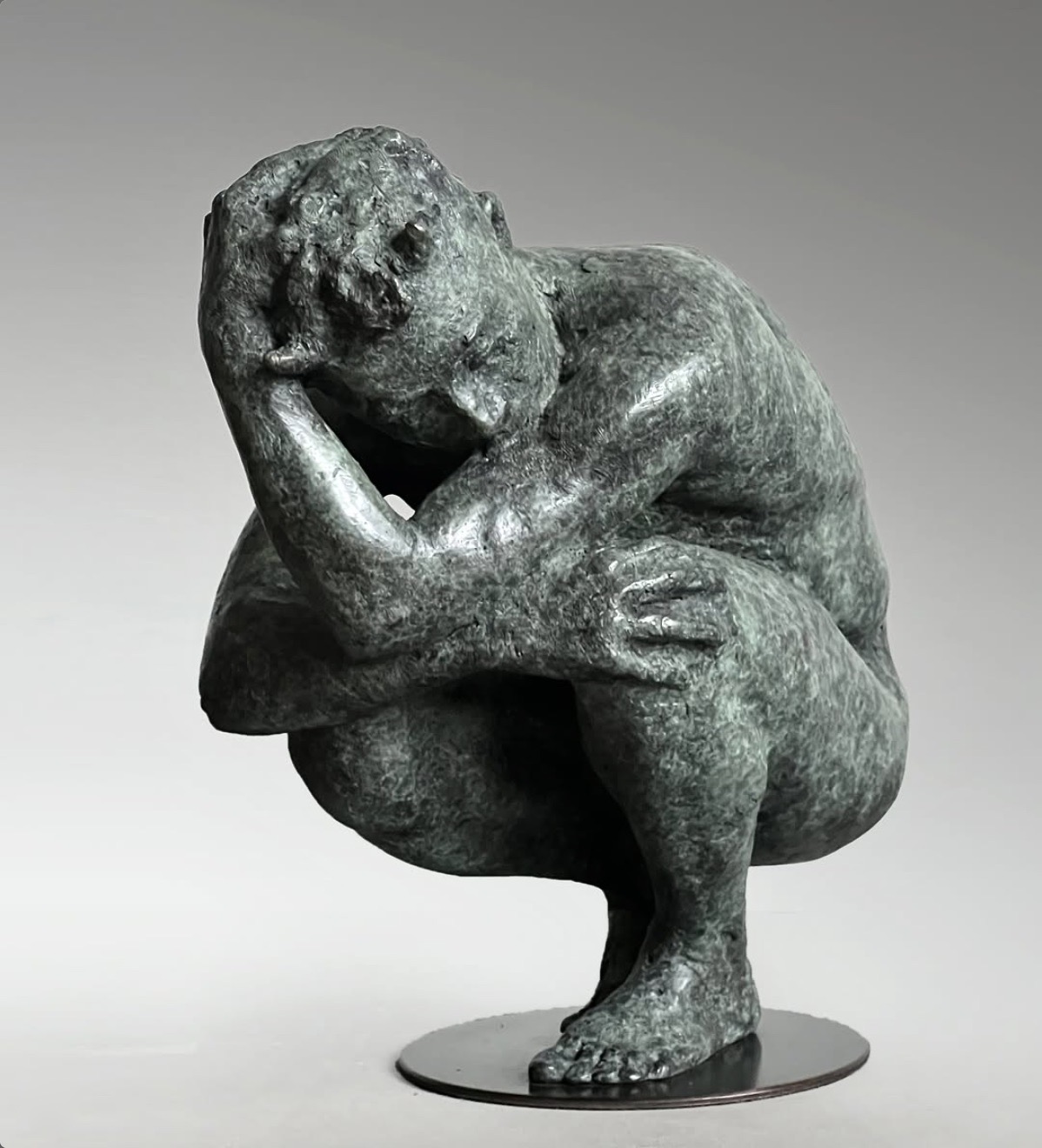

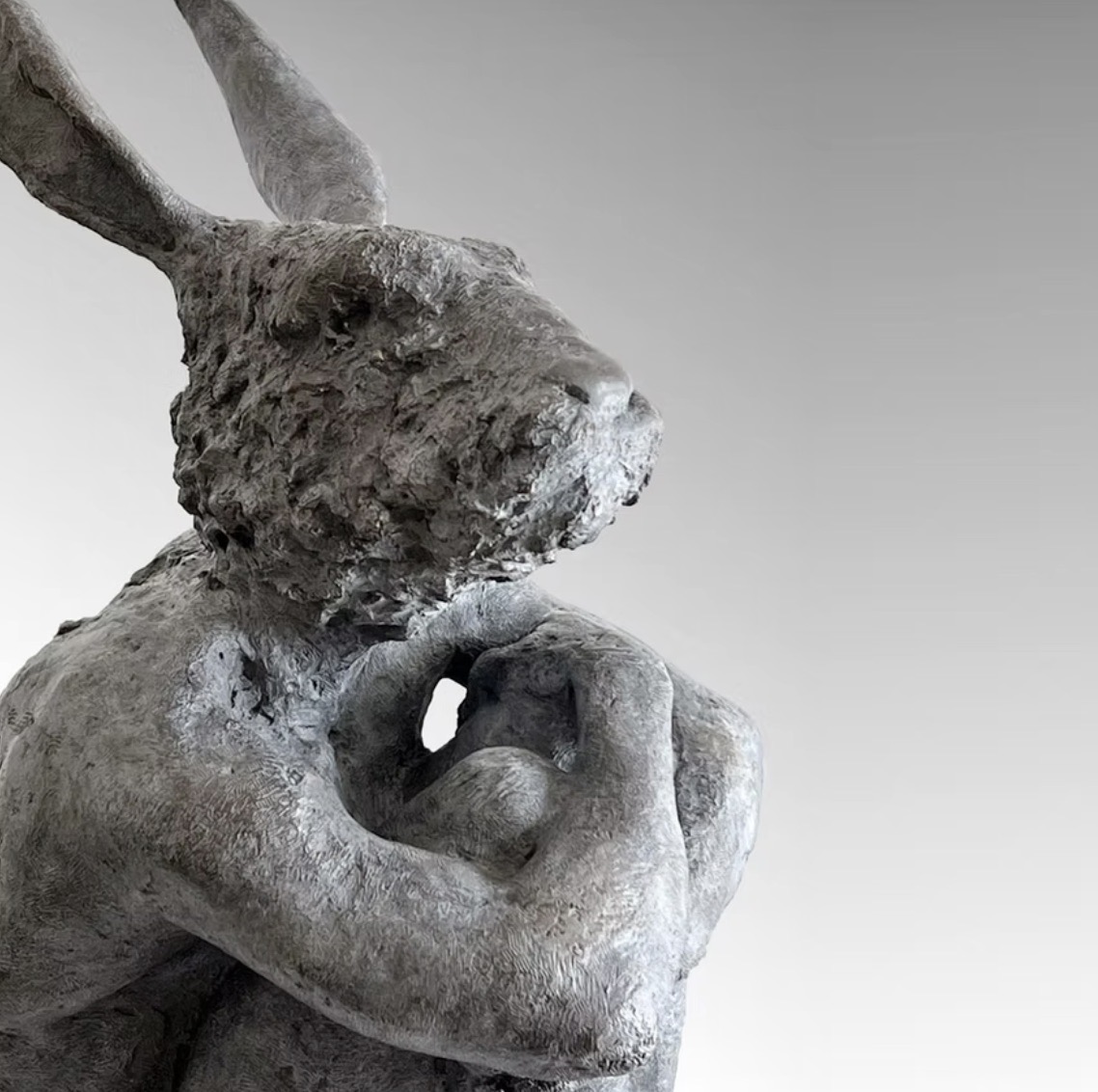

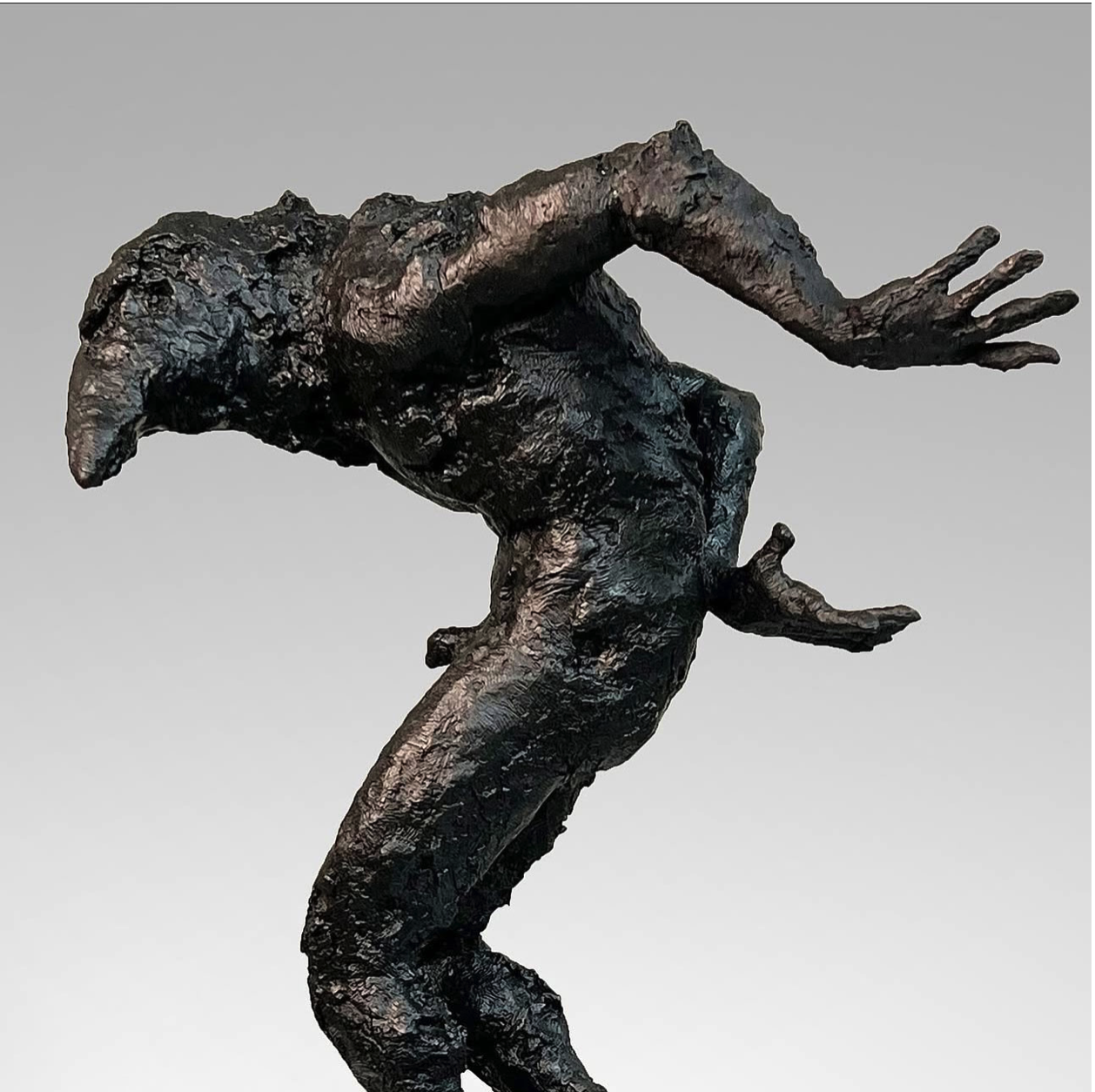

The mythical conversation in Antonio’s sculptures resonates not only something surreal or supernatural but also illustrates the beauty of the male form, and he does this with iconic symbolisms, incorporating the ideas of hybrid creatures evoking modern ideas of centaurs and deities. What evokes is the erotism and reflective ideology of the male body alongside the mythical. It’s this combination of the supernatural and surreal in some pieces that transports his work to these myths and legends and intertwines a narrative of real and fabled with subtle allegories. During our conversation as we are talking about his work, I start thinking about the Spanish Film Pan’s Labyrinth, and the iconic grown-up fable. Antonio’s work evokes the same emotive parables with hares, bulls, horses and even deer and most of the sculptures, however, centres on masculinity. The masculinity I see in his work has a powerful core, as his sculptures embrace manhood with vigour and strength, and at the same time, in a rare and uncomplicated depth, powerful but also reflecting masculine vulnerability. Embracing the beauty of the human body, however, he employs the more natural stances of thought and contemplation; added to this his rugged technique, which illuminates the allure, as its instinctive and raw. Some of his sculptures will depict the female; however, the narrative is more maternal in his fabled narrative. His work explores the mysteries of human characteristics, leading to a surrealist dialogue that is really captivating.

My first question to Antonio, was how he was influenced by art as a young person, He describes, how his parents as children of post war Spain and the Civil War were influenced, they didn’t have access to a higher education, that they always missed, so they always highlighted it to their children the importance of education and art “You know, whenever there was a documentary to be about art or anything of interest in history, they would encourage us to watch it” he recalls. He defines his outdoor lifestyle growing up in Spain with his four siblings, “We were kids from a, generation that would spend their life playing on the street and when it rained, our mother entertained us children. She encouraged us to page through the encyclopaedia,” Antonio recalls.

However, Antonio emphasises, his first real encounter with art, describing the moment in primary school, when the art teacher came into the classroom with a yellow lump of plasticine. “Basically, he just took the lump of plasticine and in front of us and to show us, look, you can make things, you can make heads. And he made his self portrait. Probably, if I saw it now, I would think that it was horrible. But at the time, I was in total awe, the miracle of transformation”. That was the start Antonio clarifies, it stuck with him all the time, and why he chose sculpture, “How you can transform matter, and give it content”. Putting the atheistic aside he explains “All the matter it can be infused with meaning, with feeling.” He explains the way we give content, and the way we attach it to symbolism and emotion, “I don’t know, but it still mesmerises me, and it’s something that has been with me all through the years, but it has marvelled me, how you can transform matter,” he continues to clarify. “That is all sculpture is, a lump of material with determined form,” he continues, “what we attach to it is symbolism and emotion”. He explains that ultimately even if it is put together masterfully, even if it is beautifully presented even if it is good, with a massive essay attached to it, what really matters is what it does to you, “We can only read it with what we are prepared to read, we read the world according to our own experience,” he tells me. “There is nothing that can get closer to people than love or hate; both feelings create an intense, equally intense bond with people. It needs to touch you, it needs to move you. You need to perceive it.”

Antonio clarifies his point further, “That’s what it is, you see, for example, now images of Palestine and it’s devastating what you see,” he continues, “You get used to it. It’s awful. I know. And, you know, it’s really dramatic, but at the same time, some of them are so dramatic and so moving, there is some strange beauty in them. Despite how ugly they are.” He explains further that in, his opinion, art doesn’t need to be beautiful.”No, it needs to touch you.”

I go back to Antonio’s childhood and growing up in Granollers in Spain, not far from Barcelona, the middle of five children in the 80’s during the financial crisis. This impacted the family, the children began to take some of the financial responsibility to chip in to contribute towards the living costs. Antonio recalls wanting to continue his education and enrolled in evening classes to learn English. Then two years later, he had to join the army, which was compulsory in Spain. “It was the most devastating experience in my life because I felt so frustrated.” The experience left him determined to continue his education. After leaving the army at 20, he enrolled back into secondary school, working a full time job, and going to school between 6 – 9 pm, hoping to obtain a university entrance. Despite the obstacles of working full time and being scholar, he had the determination to get an education. “Throughout my years, all through my youth, my refuge was playing with clay”. He describes how at 12 he received a lot of praise for a sculpture he made, that acclaim and strength he gained from that artwork, gained an appetite and making clay sculptures that became his refuge. “You know, some artists do art because they have an ambition, because they have a concept, but for me, it is a refuge”. Antonio then continued working full-time doing any job, between a salesman to working in a factory.

After graduating, he attended the University of Barcelona, where he additionally worked as teaching assistant, which included experience working in the University workshop in the foundry. His five-year degree in fine art led the way for the Erasmus Grant, to study at St Martin’s in London at the age of 29. He recalls how much he enjoyed this period; he additionally had a grant, so he didn’t have to work full time, and recalls socialising in London. However, he returned to Spain to complete his Fine Art degree back in Barcelona. I asked Antonio how his parents reacted when he told them he wanted to go to university and study. “He recalls his father saying “oh you are stupid, we are poor”. It was when Antonio received five honours, that he recalls his father starting to understand his son “and he started believing in what I was doing” Antonio explains. “it felt like I had a calling”. “My mother was the most encouraging woman, and she always said, that you have to follow your instincts and dreams and your hearts desire” he smiles. “Now my siblings fight for my sculptures,” Antonio says with a huge grin.

We start talking about his voice in his work, this combination of the animal and the human, “I grew up through the Franco dictatorship, and the access that we had to cinema, TV, literature, everything was very edited, by the regime,” Antonio emphasises. He recalls that most of what they watched were westerns or films about the Roman Empire or Greek Mythology. “So automatically, you get exposed to the classical world in a twisted way because it was edited,” he explains. “Nowadays, we differentiate between nature and humanity, which is really stupid because we’re all one thing, and over the history of humanity, if you look back, throughout, there are symbols and mythologies, all across the world with those Hybrid figures. We have always used animals to depict traits of humanity,” he tells me. He explains that there wasn’t a divide between humans and animals; if you look at cave paintings, the way they would symbolise and they would connect to the unknown and to the cosmos. Antonio continues to emphasise that by depicting animals and hunting. “Probably doing it as a way to appeal to the ghosts for a hunt.” But it was the animals that symbolised everything he explained, “In Mesopotamia in Asia, or South America, we have that hybrid figure. We have always used animals to depict traits of humanity”. He elaborates on the monks handwritten books, translating the Bible and the richest text on that, “And you’re going to find some anthropology studies and understand better why these hybridisation of humans and animals were created, “You find it in all ancient civilisations”.

Antonio explains, how working at the foundry to help fund his studies was the evolution of his work, he describes the emphasis of concept art and how it was pushed at university, however the foundry and the artists with whom he worked, whose work was figurative and abstract, initiated what Antonio describes “Opened the gate of the whole kind of kind of mythology with animals” furthermore his instinct when working. He explains he doesn’t plan his work, that his sculptures evolve, in an instinctive way, he never knows what will come about when he has the clay in front of him, it’s all emotive. There are parallels to his hare sculptures, he tells me about the mystique of the hare, “They are very difficult to pin down, and kind of solitary creatures”.

As we come to the close of our chat, I ask him what or who inspires him, “Of course, when I was young, I was in love with Michelangelo. Where I truly find my inspiration is a conversation with a friend, a piece of music, the effect of daily experiences big or small, that for some reason trigger the process. It is like the vibration after a musical string has been pressed and the vibration, even when the sound is not perceptible, carries on expanding. Some ideas evolve fast like a tsunami while some just linger and brew slowly for a long time to then sprout.” I ask if he could own one artwork, “It will have to be a painting by Bacon or Velazquez.” How would you describe your style? ” I really feel like I haven’t started, that there is something that I haven’t managed to pull out”. When I ask what he considers perfection, he tells me that perfection is a mirage; it doesn’t exist.

Interview: Antoinette Haselhorst