Barbara Kuebel

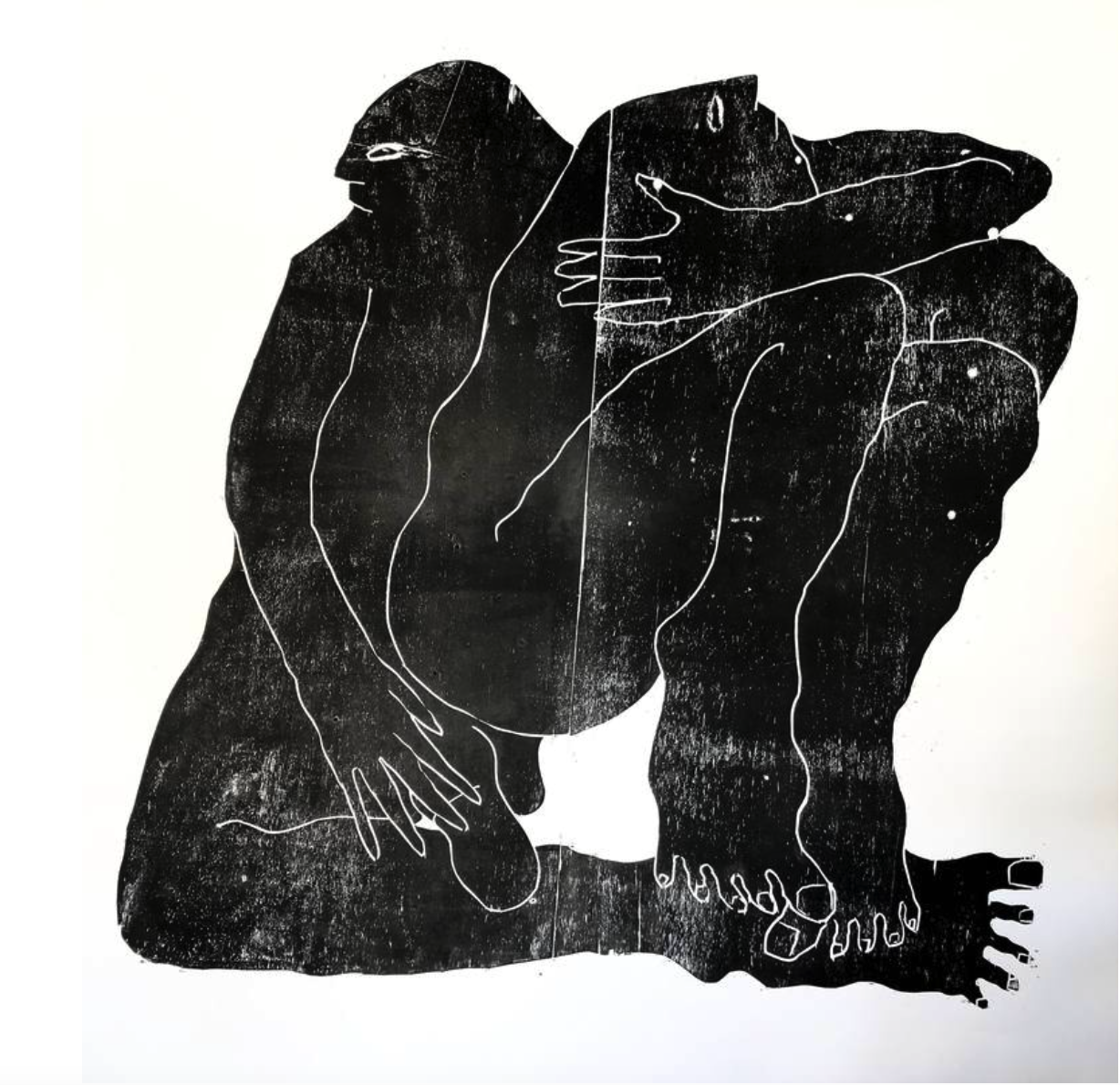

What fascinated me during my meeting with Barbara, was how she described the kind of narrative that isn’t important in her work, that she doesn’t consciously narrate an idea or concept, however, the abstract expressionism in her work is an all-consuming narration, of human interaction, the dialogue often represented in closed spaces. She speaks fast, as she describes the blank canvas. She describes her artworks as a flow, and nothing is planned, the flow is almost reminiscent of surrealist automatism, however with the defined lines that she has sculptured with a blade on the wood. These printed wood carvings; the sculpted art of engraving into wood into a relief format and printing by hand onto paper, evoke an element of European folklore and myths in the systematic structure of her art, her character’s symbolism often reveal a spirit reminiscent of goblins, hinting at Luba art with its origins in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Her characters with oversized feet and hands reflect the emotive responses of people in confined spaces and situations, there is an overwhelming intimacy, that is both relatable and abstract, her choice of monochrome colours such as black or one tone of yellows, pinks or gold, however resonating this call of multiculturalism that is both relatable and unique. Barbara highlights the art of printmaking, how it should not be the smaller sibling of painting, this is an old style of printmaking, you have to be very clear about your editions, she tells me, the print involves the action of the artist, she emphases.

In contrast, the abstract expressionism in her paintings on canvas engages a similar analogy, however energetic with vigorous parables, recently termed action painting. Barbara is born and raised in Austria, she recounts an idyllic childhood, describing her parents as a working mother, and emphasising the independence that was encouraged in her as a child, she describes how as a five year old she would cycle alone to meet her mother at work and cycle back home with her, “Which would be unheard of nowadays” she sighs. Learning to keep herself busy she recalls, “My parents were never helicoptering me,” she tells me, she learned to keep her own motivation. As a teenager, she already started experimenting as a figurative painter, and at school, she was given the name the artsy one, it was clear which direction she was going in, and she started to apply to Fine Art Universities. However, Barbara emphasises the complexities of the application processes, and how the universities rejected the perfect portfolio “they looked more for the maturity of a person with a strong personality, more of a rough diamond, that would bring skills and a way of expressing yourself”. Barbara describes her tutorials were almost nonexistent, the tutor appearing once during a semester and discussions about the topic would take place, and students would have to find their own track, she explains. She has two degrees from The Academy of Fine Art in Vienna.

We talk about her technique, Barbara describes over-painting her work when she doesn’t like it or throwing them away, and that she doesn’t hoard work she is not happy with. She over-paints what she considers perfections, as she explains her disdain for perfection, “It should not be too perfect” she emphasises, describing what she believes, “the most important part is being a risk taker in art, you might overpaint it, but you learn from it.” Her journey as an artist, was over overcoming what Barbara calls being a mature artist, she describes being a mother and having a family, “You are not supported as a mother in the art world” she exclaims, with the image that you cannot dedicate yourself to art. That the image of women in the 70’s where we were much stronger and we were liberating ourselves, she feels she had the opposite experience with her three children. She explains the dualism, and quotes in German the ‘Gretchenfrage’ which essentially is from Goethe’s Faust, which translated means, a crucial question that usually has a difficult or unpleasant answer. Barbara describes galleries coming to visit her at her home, and seeing her children and husband, and how they initially would presume her husband is the artist.

Currently, Barbara lives with her family in the UK, just up near Lincolnshire, having spent most of her life traveling and living in different places with her family. The range is extensive, with all experiences and how they impacted her and her work. From living in the Netherlands and Switzerland to São Paulo, Brazil, she describes London as a little village compared to São Paulo, how she embraced the city’s accepted multiculturalism and that nobody is put into boxes, compared to her experience of living in the deeply conservative Alabama. Barbara delves into the experiences of learning different techniques in methodology from each country. She describes, how in South America the art scene is derived from a lot of heritage and tradition, you have to adjust to the fact there is less freedom as there are fewer art materials to choose from, and she started to use the local wood for her carvings, how the material defined her work and now this wood is all she uses for her carvings. Recently, she became part of Xylon, the society of wood engravers based in Switzerland, Barbara being one of the youngest foreign members along with the other 35 established artists, however most importantly, Roma Signer, a very prominent contemporary artist from Switzerland and Claudia Comte.

We talk about what who inspires Barbara, she mentions artists Salman Toor, Georg Baselitz, Markus Lüpertz and Caravaggio, mostly artists after WWII. She then interprets her works narration, describing those feelings around social situations, being uncomfortable or being anxious, and explains how she doesn’t want to stand for a community, rather sees it, as I am here as a person but not as a woman. Last year during an exhibition she had in New Orleans at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, she developed the concept, to concentrate on what happens between people as two individuals. She asks the question “What are you?” why do we face challenges with other people and why do we get on with one person and not another? “It represents the part of yourself that is not honest and true, and how we try to be someone else with some people, mostly those we do not click with.” I asked her what is really behind her work and what she wants to convey. “I wanted to find out something about myself” Barbara explains, sometimes she feels she is a bit of an actor, describing her images as being a bit erotic. That she feels the debate of erotism in art should be discussed as a medium, of how people deal with this form of communication. “You can talk some things to pieces,” she tells me in German. It made me think of the book Ulysses, by James Joyce, watching the documentary about the book and its first publication, how people reacted to the eroticisms in the book when it was serialised in the United States and subsequently banned in the UK and the US, the entire work first published in Paris. “You can express yourself, but can’t express yourself!” Barbara exclaims.

She is currently exhibiting at Jonathan Ferrara Gallery, in New Orleans.

Interview: Antoinette Haselhorst