Delphine Lebourgeois

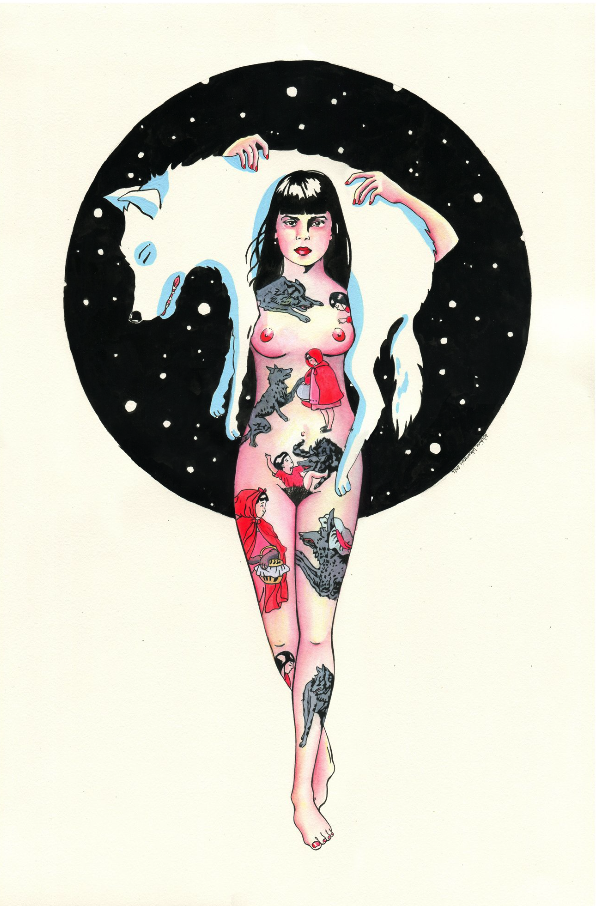

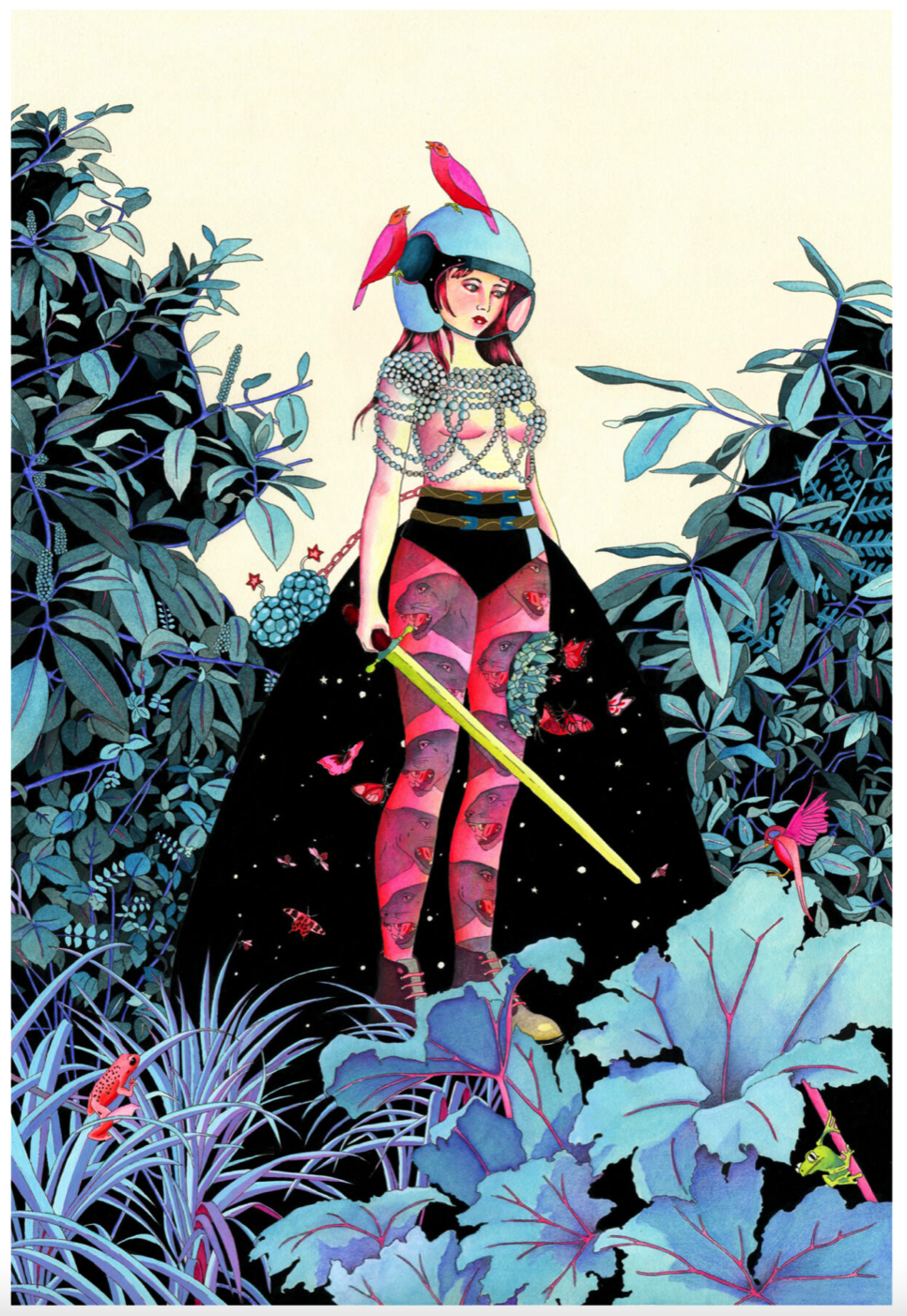

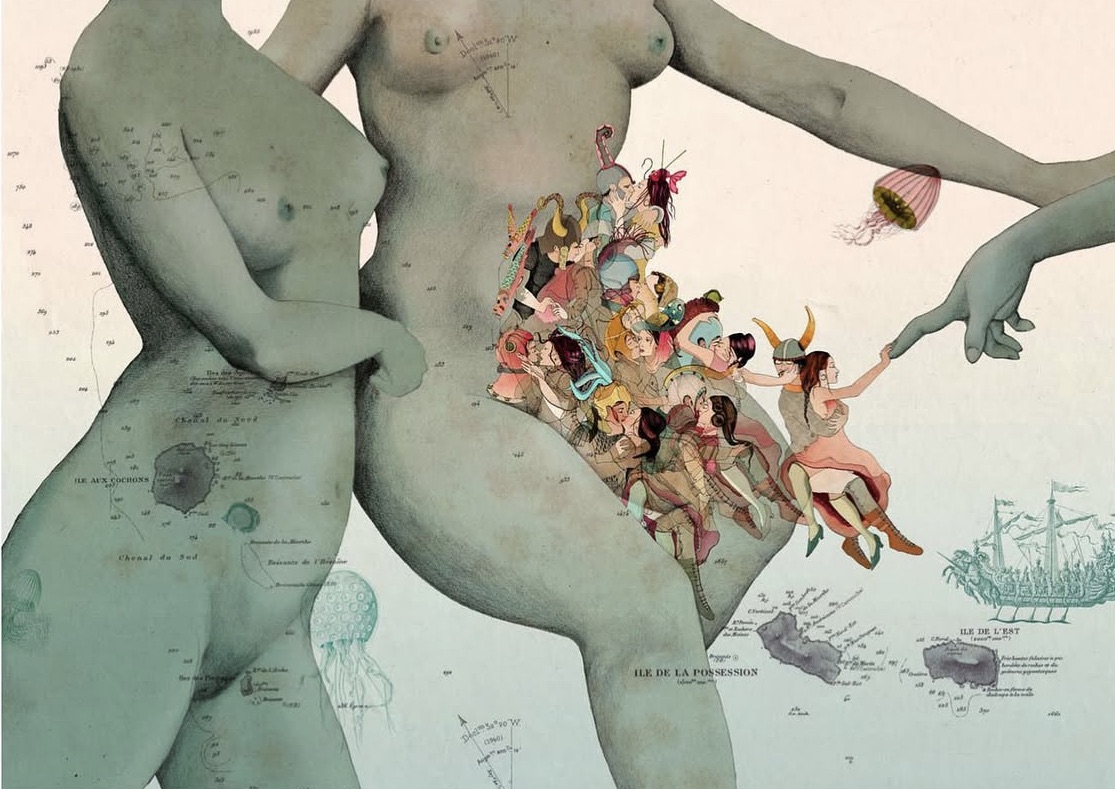

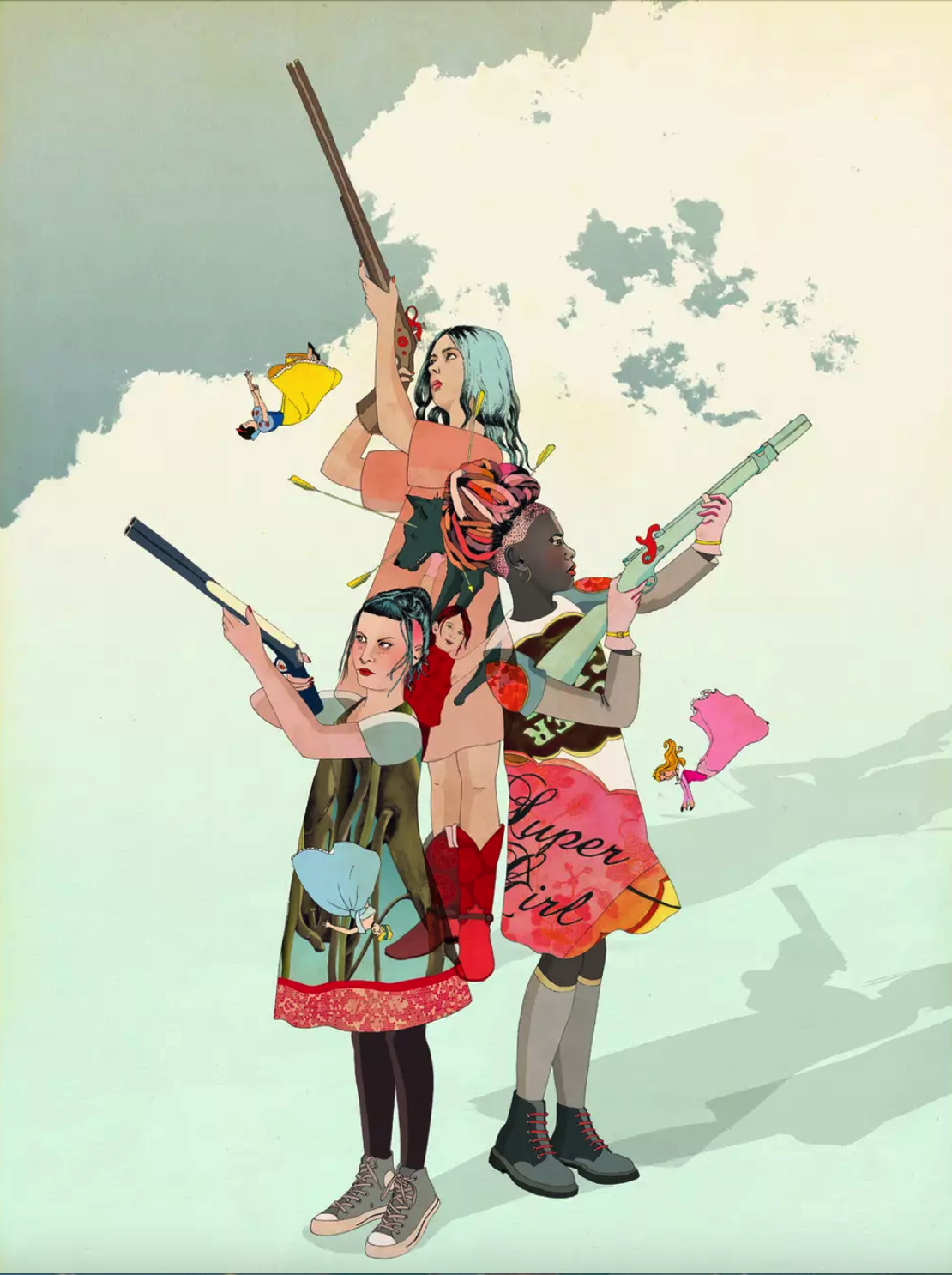

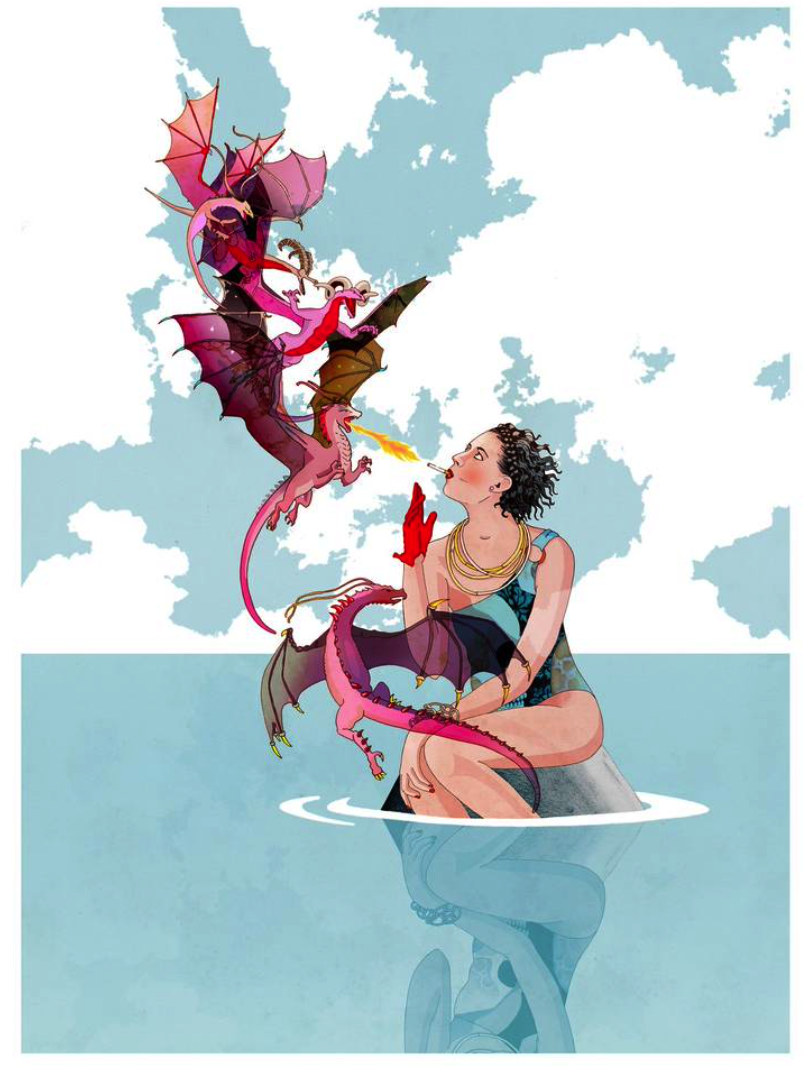

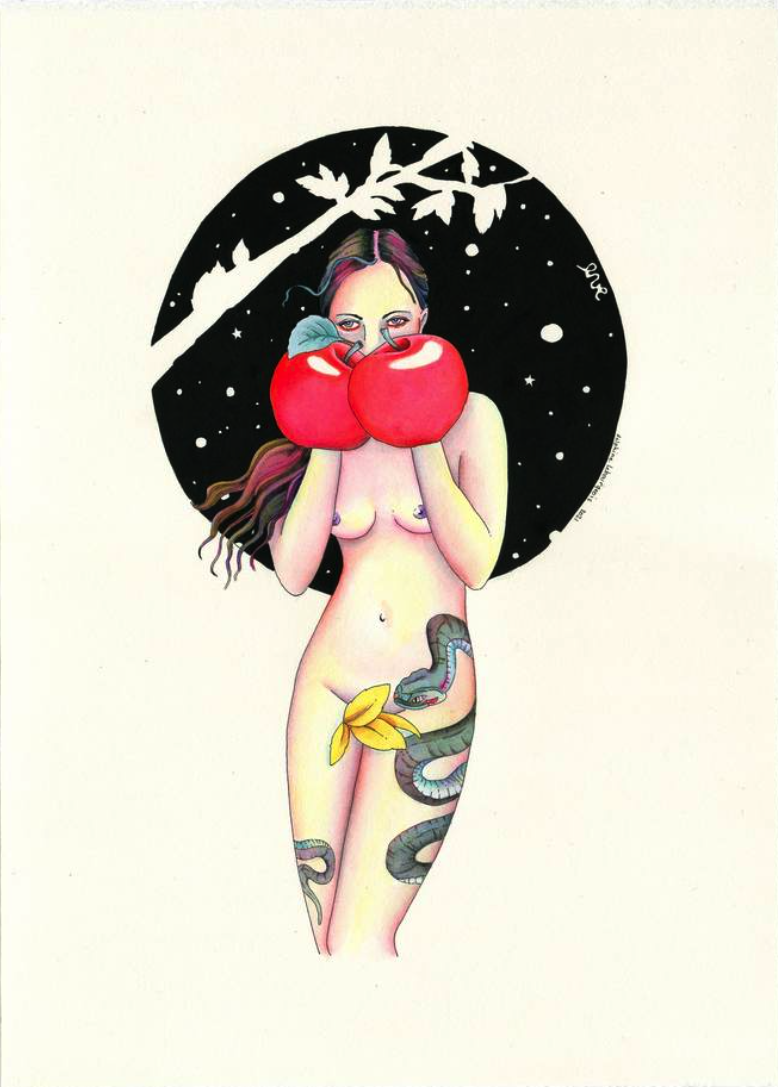

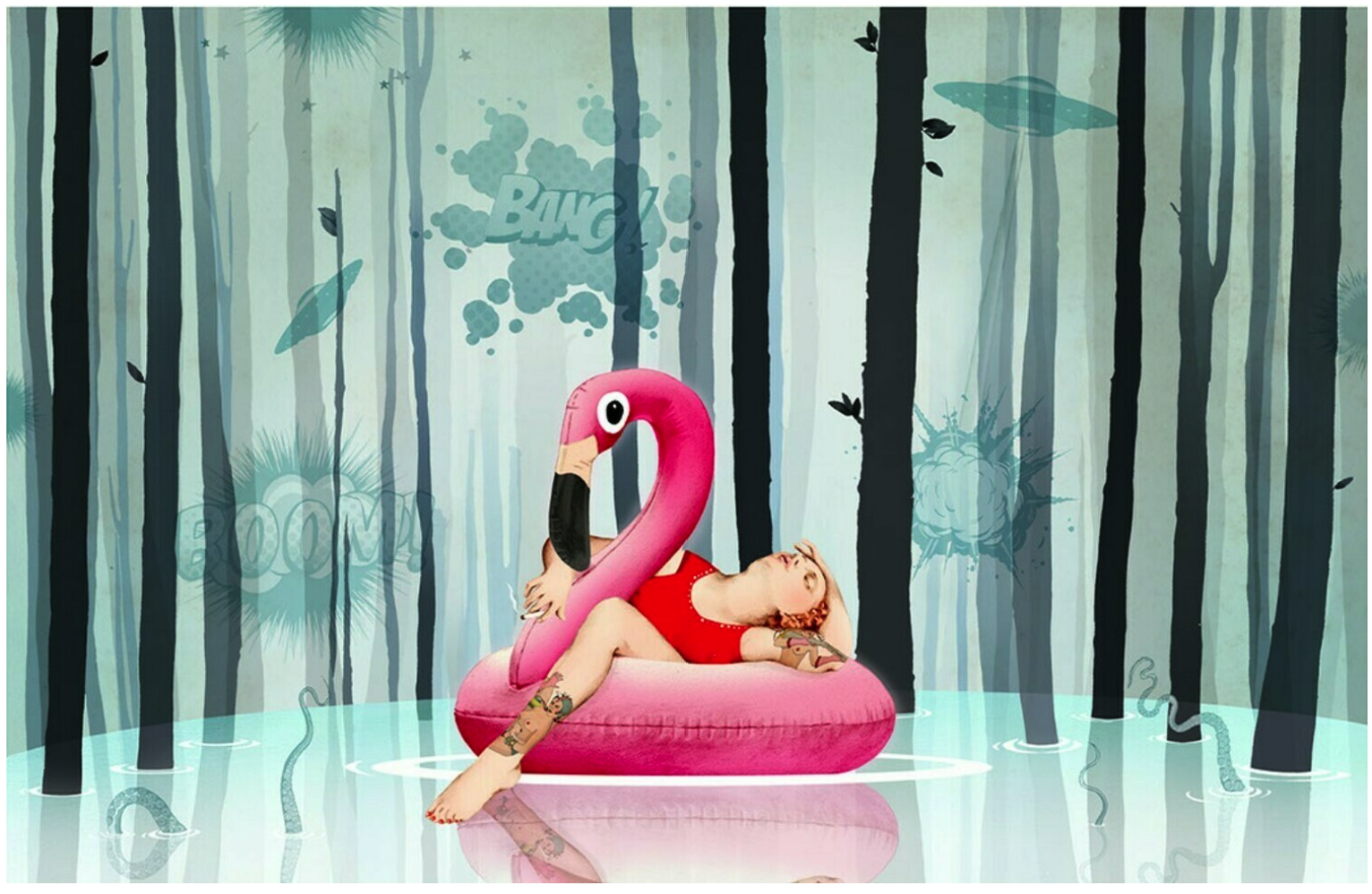

There is a story of female empowerment floating in an indifferent portrayal, stylised amongst the pinks, greens and pastel shades of warrior-smoking powerhouses of women. Delphine’s artworks delicately painted in these old-school feminine hues are an individualist life-wire of power and mutiny with the endurance and the encumbered labour of juggling it all. The initial beauty and refinement in Delphine’s detailed extensive illustrations are a narrative of something so subtly intriguing, it looses itself in an intrigue of nostalgia, however, her artworks are a deliberate chronicle of her ability to tell a story, not with words but the illusive and quizzical illustrations. I say this because her drawings illuminate the scope of literature, politics, and the references to influence and propaganda. Her intricately detailed illustrative portrayals of female individualism, are so cleverly constructed they imbue the archetypes of females over time. She relays the cathartics of rebellion and the emancipation perceived of what it means to self-destruct, symbolising liberty and revolution. Her artworks of women smoking amongst other mutinied acts of defiance, and how these actions at the same time, are to breath in deeply to find serenity, as she embarks on a dialogue of history transcended with the journey of women and society as a whole.

Delphine tells me about her upbringing in Clermont-Ferrand a town in the centre of France in the middle of the mountains, “So lots of nature!” she exclaims. Her father is a plumber and her mother is an administrator, she describes her influences in art, she tells me about anime, Japanese-style cartoons, and Manga graphic novels and comic books. Additionally, her love of literature, poetry and describing her teenage years as reading a lot, her interest in SciFi books, the idea of storytelling impregnated itself in her, and her desire to tell stories, spending a lot of time writing as a teenager. It was her art teacher that encouraged her towards the arts, and motivated her to write stories. “I loved Greek and Norse mythologies as well as biblical stories” she explains “My room was decorated with genealogical trees of Greek myths families and Arthurian Legends.”

She does recall getting a lot of grief from her family at first with her choice of art as a career. However, her parents were always supportive. She completed a BA in Fine Art, at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. She recalls one of her tutors, the artist Bernard Frize, “And how it bothered me because the discourse about the work seemed to be more important than the work itself. I wanted my work to be self-explanatory, but my tutors’ approach also gave me a certain discipline. Everything you choose to use in your art needs to be justified. I’m very grateful for that.” However, the impact and benefits of this, are now what she utilises in her work. “At the time I was doing photography,” she tells me, her first love of photography, describing her love of the dark room, spending hours experimenting, and then drawing came much later.

Delphine tells me about her trip to Vietnam for six months, and how this changed everything, she describes it as a sort of loose exchange, visiting Ho Chi Minh City formally known as Saigon, her best friend was going, and she decided to tag along. She took her camera, but she didn’t have all the materials for a dark room, and she started drawing instead, all she had was a pen and paper to express everything, she describes the experience as a real culture shock “I had never been outside of France, I had a lot to say, that’s when drawing came in” she explains. “All the little sketches and doodles communicated something. It’s always been about ideas for me. So I had an idea, something that, you know, shocked me or something then and I was translating it into a little drawing, but they were all tiny sketches, really tiny quick doodles. They were immediate and they communicated something”. Delphine describes what she witnessed, what she saw, the indecency towards children, the sexual ascent of their lives, the prostitution, nightlife, people with limbs missing, and children sleeping on the streets, it was 1997.

She moved to London in 1998, during this time, “I worked little jobs, mainly as a receptionist for a GP,” then she met an English man and had her daughter Juliette, born in 2000. Delphine never stopped drawing and enrolled in a Master’s at St Martins in 2003. She applied with her children’s book illustrations, photos and drawings, however, it was the two slides of her drawings of Vietnam of the child prostitutes, that got her a place at St Martins, they had an impact. “Saint Martins were really conceptual as well it made me question the boundaries between art and illustration. For me, an illustration is answering to a brief, like not working alone, while art can be really anything. It doesn’t matter how the image looks or whether you’re using communicating tools to communicate an idea. Art is freedom. That prospect can be daunting, but it is mostly super empowering”.

Her daughter was three years old when she enrolled, and she gave up her job at the GP, “It was a tough time” Delphine explains “having a small child whilst studying and also working part-time at the Association of Illustrators”. After graduating, she started working as a freelance illustrator mostly for the press. Her first commissions were for the Guardian. “You really learn how to draw, not as polished, a lot of it was raw” and she learned from Photoshop, how to work with illustration, sometimes she had to produce three images in 48 hours, with a brief, there was a lot of pressure and a lot of stress, working for the press. “The pictures need to be produced and there is super fast turnaround it was really full on” she exclaims. “I did a lot of book covers too, it was when I met Gina Cross”. At the time Cross was art director at the Guardian, who started her own gallery “A Little Bit of Art” . Delphine started to work with her and sell her personal work, which grew really quickly, she tells me. Subsequently, her work started appearing at art fairs and it’s all taken off, it happened all quite fast.

Then we talk about the inspirations, what and who inspires Delphine, she pauses looking up thinking, “Other artists, books, films” and pauses again “And what’s happening with me !” describing her own experiences. Her favourite artist, Delphine contemplates this question at first, and then she exclaims Maria Abramovich, because of her braveness, her ideas and inventiveness, we talk at length about the artist’s installation work at the Royal Academy. Delphine’s current body of work she is working on is called ‘Play’. She describes it as about having fun, “I’m kind of going back to something very irreverent and playful and I’m drawing on different materials” and that she is taking her time on this series. We talk about what factors allow her to love an artwork, “I am drawn to ideas, humour and aesthetic”. What does she consider perfection “Definitely not sure that it exists,” she says. What does come to her mind, is a movie because there are so many aspects to a movie “You’ve got the acting, you’ve got the major cinema photography, the sound, you’ve got so much, in order for that to be whole and to function, you do need like something magical”. Then we discuss the best and the worst in the art world. “The best in the art world is doing art fairs and having conversations and the worst, is the over-inflated art prices” she exclaims. However, if she could have any artwork what it would be “A drawing from Henry Darger or Pool of Tears 2 by Kiki Smith” I ask about her challenges in her creative process, “To come up with the ideas is the most enjoyable, the challenge is making it work visually…I throw a lot in the bin and I’m very slow”. I asked her what she considers her greatest achievement so far, “Still standing up as an artist”.

Interview: Antoinette Haselhorst

©️ C-A-K-E Contemporary Art Keen Enthusiast Ltd. All rights reserved.

Excerpts permitted with credit and direct link. Full reproduction prohibited.

One Reply to “Delphine Lebourgeois”

Hi!!!

Sherine Thompson here, I saw some of your artworks and pieces online …I must confess they’re really captivating, and eye catching…if you don’t mind I’ll like to add them to my collection for an upcoming auction,

So are they for sale?

Looking forward to hearing from you my email address: sherinethompsonart@gmail.com

Best regards

Sherine