Sam Shendi

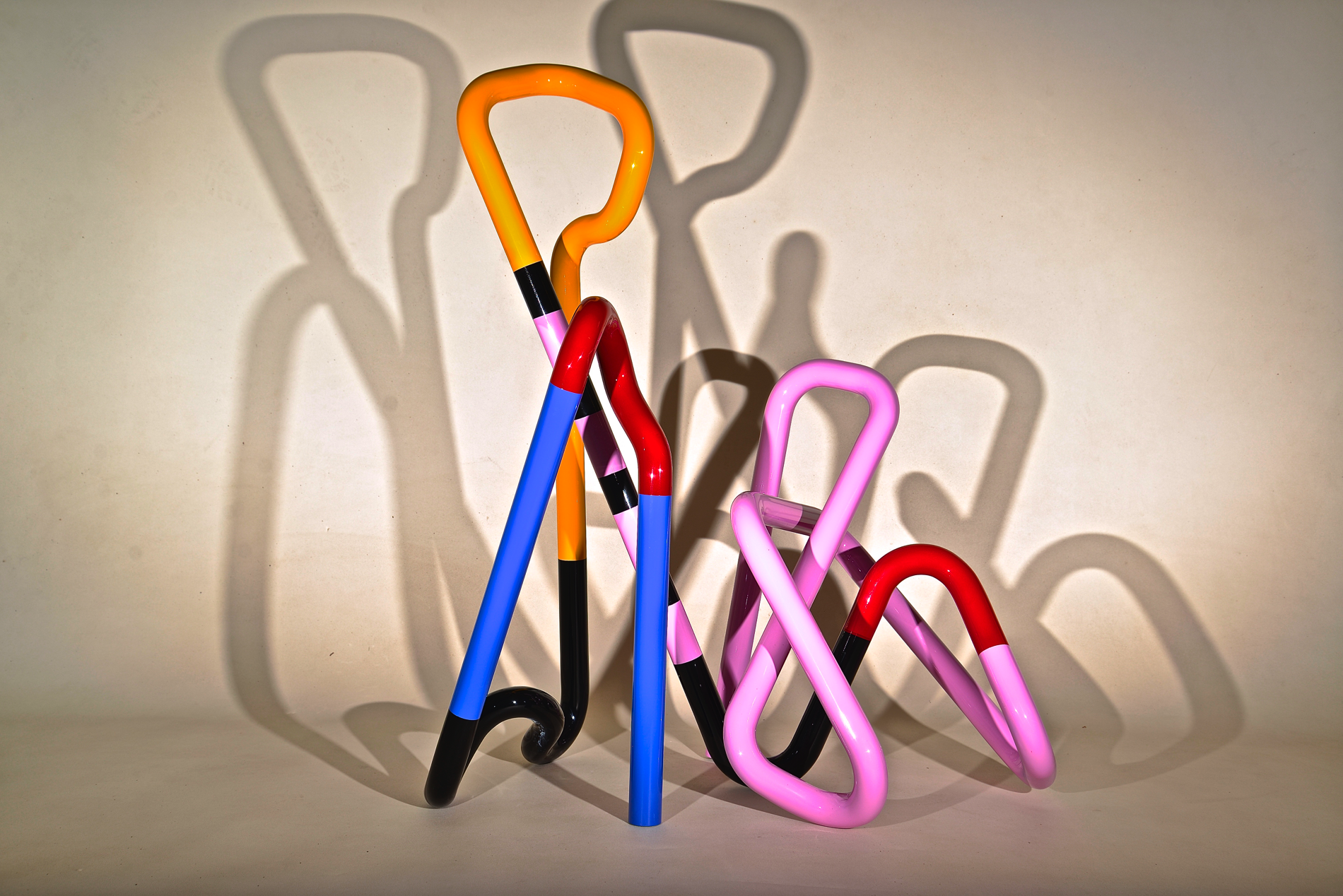

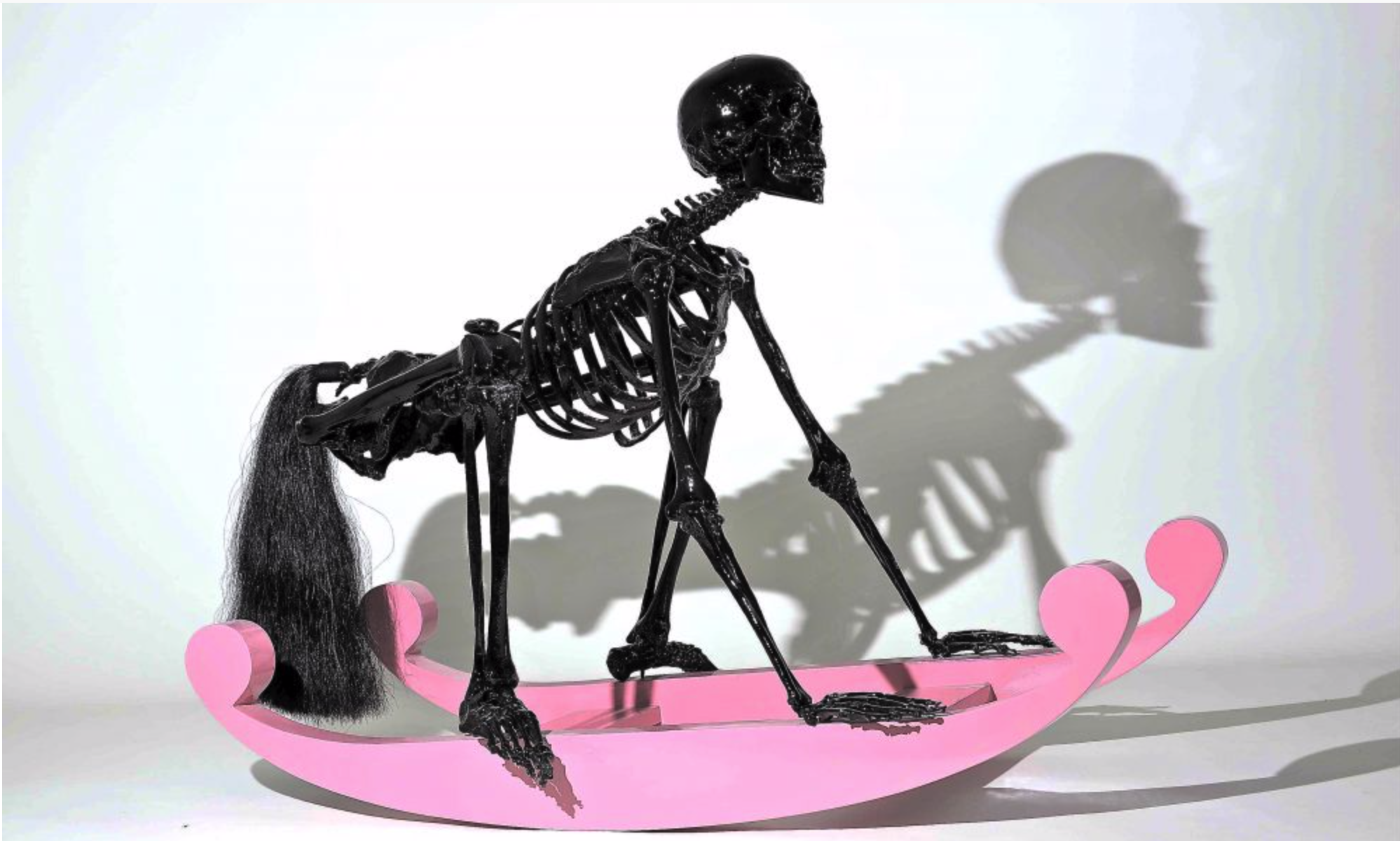

Sometimes contemporary art just makes you smile, whether it’s the wit and intelligence, the humorous pluck that an artist creates something incredible with just lateral thinking. Sam Shendi’s humour and vibrancy in his work has an emotive complexity. His most recent sculptures, from his ‘Harlequin’ collection, have an anthropomorphic style, they resonate the imaginations of childhood, the fictitious characters that sit in children’s dreams or story books. ‘The Dream Catcher’ six different artworks, a crouching humanoid creature with horns in pillar box red, or striding in cobalt blue, the wide smile on two legs in coloured stripes anchored in black socks, or the figurative half human, life sized in stripes. Combined with the subtle attention to detail, with little birds, the whole has an overwhelming presence of power. As if somehow something is unconsciously evoked in you. His artworks are a mystery of imaginings, all the colours symbolising meaning; green is innocence, blue is in “being blue” and red represents anger or sexuality. The artwork ‘Defeated Butterflies’ a powerful political narrative, a life-size bright green bull, that symbolises government. ‘Fragile’ a colourful representation of a shire horse in blue. His ‘Calligraphy’ series or ‘Paper Cut’ sculptures in ‘liquorice all sorts’ colours that almost resemble Mondrian’s paintings come to life. The artworks playing with light, projecting differing characteristics as shadows.

The contorting shapes in his sculptures encapsulate the complex relationship between mother and child. That hint on Shona art, these metaphysical shapes, portray the bulbousness of late pregnancy or the co-dependancy of young children that cling to us. His ‘Giant’ series, these real life giant, colourful, shiny, bold and playful artworks that are everything but straightforward as they embrace the abstract, resonating artists like Henri Moore and Miro, in a unique contemporary lacquered finish. The range and complexities in his diverse artworks are surrealism in vogue. The influences don’t really matter, as this Egyptian born artist explains, “as a student you are like a seed” he tells me, that the world doesn’t need another of the same artist, you must not stick to one style, but keep creating your own.

After graduating in Fine art from Helwan university in Cairo in 1997, he didn’t work as an artist, instead working with a prestigious interior design company, whose clients included the president of Egypt, and then setting up his own interior-design business near the Red Sea. His father told him, artists only make money once they are dead; there is a hierarchy that you don’t argue with, he tells me smiling. There are differences between the cultures of Egypt and the UK. Explaining that, only when he left Egypt, did he know Egypt. How he embraces growing older, as he thinks experience makes an artist, and how he relates to the complexities of culture and why people are always drawn to the past. This is part of his philosophy, and the relevance of it is in his work.

Sam spent a few years travelling around the Middle East and Europe and made his way to London. In 2000 he made the choice to settle in the UK, spending time in London, then moving to Yorkshire, where he met his wife; they now have their own family. For a long time Sam turned his back on art, not looking or working in the world of contemporary art for 10 years. His first exhibition in 2010 in London, of his metal works, are his journey out of depression, a subject matter he is all too familiar with. Describing the cultural differences of growing up in Northern Africa, home of the Pyramids and his complex relationship with his family life, the middle child of five children. Now a father himself, he understands a lot more about being a parent.

He moved away from the stainless steel collection in his first body of work. Inspired whilst watching his car being repainted, the shiny, smooth colourful finish, that doesn’t fade and can permanently hold its own especially when displayed outside. Sam emphasises that he studied architecture and engineering and how it’s essential for the work he does, the sizes and scale, you have to understand how monuments are made. He doesn’t disclose too much detail with the secrets of his methodology. He works with a welder and the man who painted his car and that his sculptures are all hand carved. The artworks are covered with fibre glass, resin and a high gloss mix. He mentions Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons and Anthony Gormley who have a team of people making their works. In the 10 years, Sam’s extensive bodies of work have travelled the world. Currently his work is being exhibited in Johannesburg, and another show of Mother & Child to be revealed soon. He has won numerous awards; the W.Gordon Smith & Mrs Jay Gordon Smith Award 2020; The Liverpool Plinth Winner of the Public art award 2019; the FIRST@108 Public Art Award and the Royal British Society of Sculptures. Exhibitions in Scotland, London, Portugal, Germany, Belgium, in an array of cities, and prominent locations, his works displayed together with art royalty such as his own inspiration Henri Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Peter Randall. He has an array of private collectors from around the globe.

Sam, talks to me about creating his artworks, that you feel like you are a god, making the art, and when his work is done; how it’s essential to move it out of the studio, into a container. So it doesn’t influence his next piece. His creations are not made to make money, that they are an emotive diary of his life, and that he is not a salesperson. It’s only when the art is in the gallery or photographed that he can see the value. His humility is evident when he explains why he prefers to live in Yorkshire instead of London. London is a jungle he tells me, and how Yorkshire men and women leave you alone. However, he enjoys how the occasional farmer that may come by and look at his artworks standing outside his studio, asking questions. This is what it’s all about, Sam tells me, as soon as you question an artwork it’s made an impact and has you thinking, and that is the power behind the meaning of art.

Interview: Antoinette Haselhorst