Fin Dac

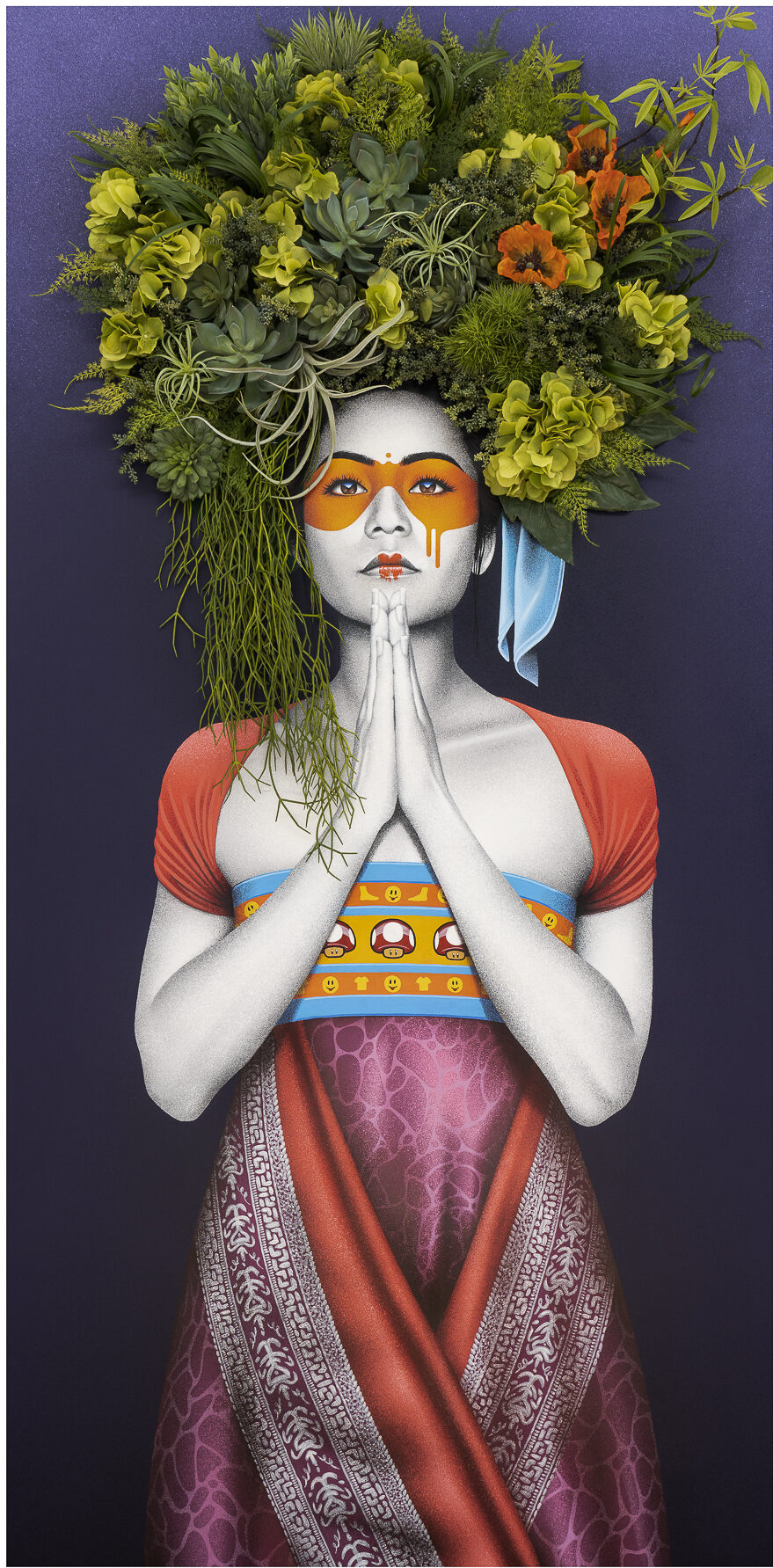

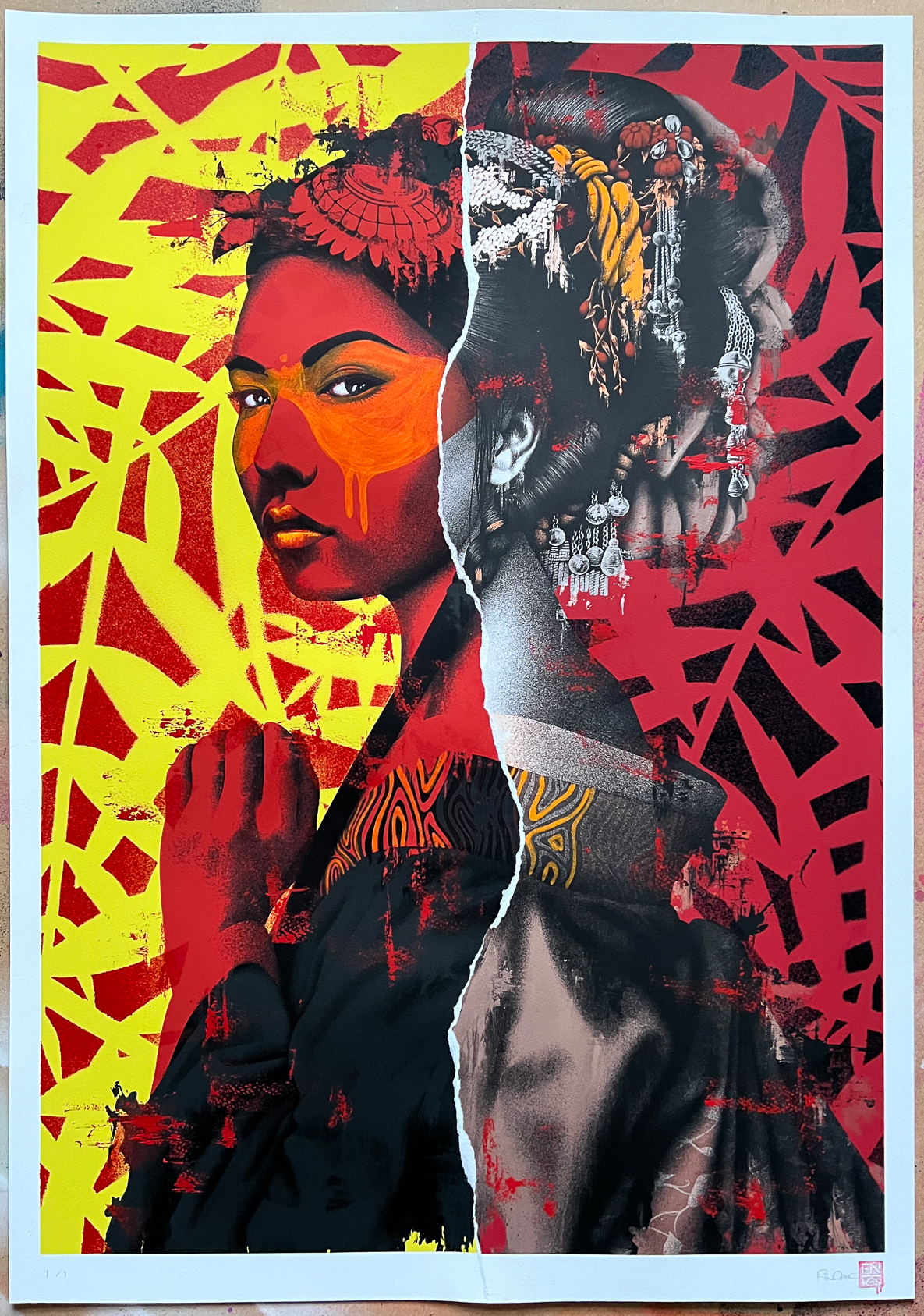

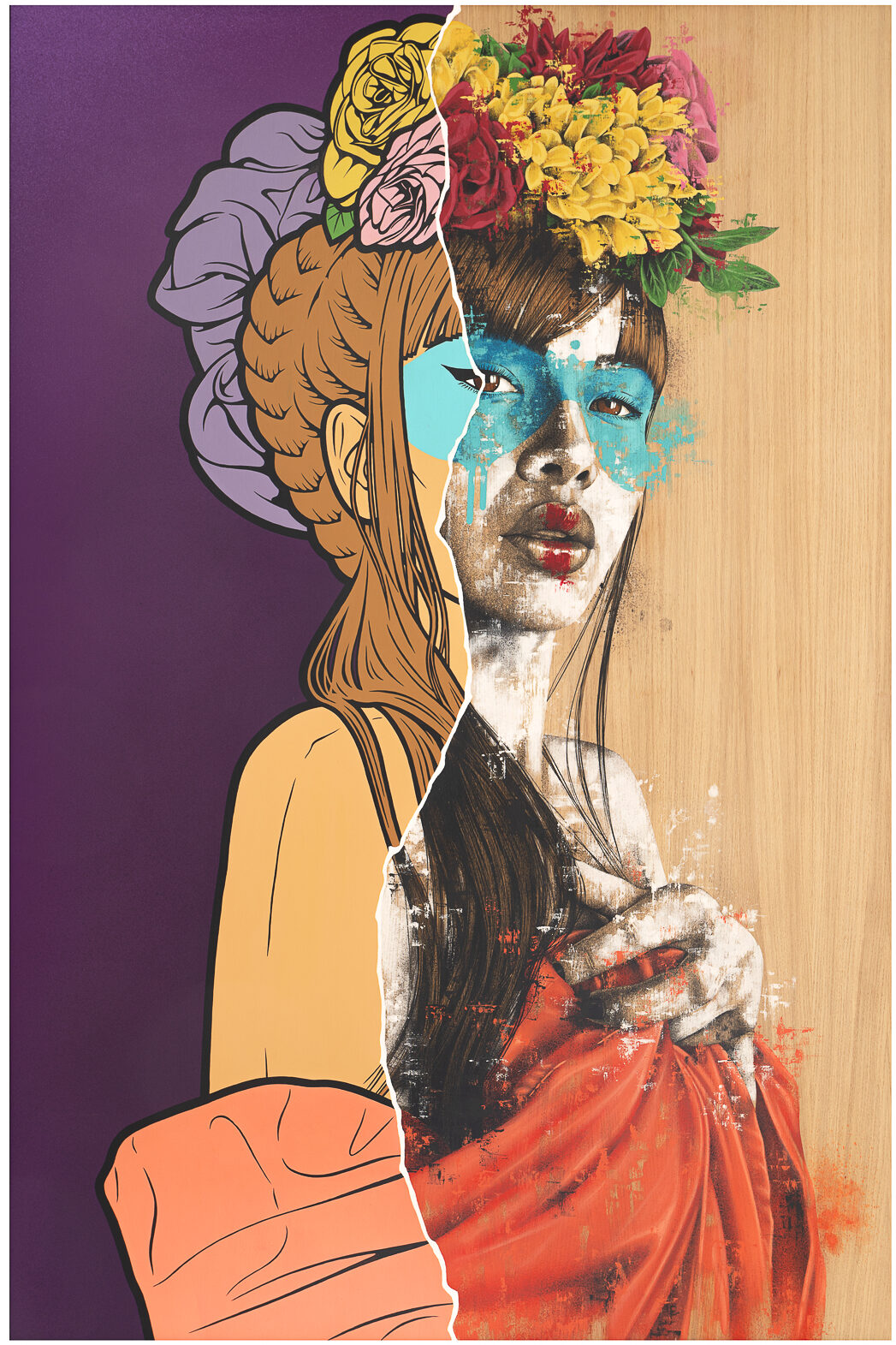

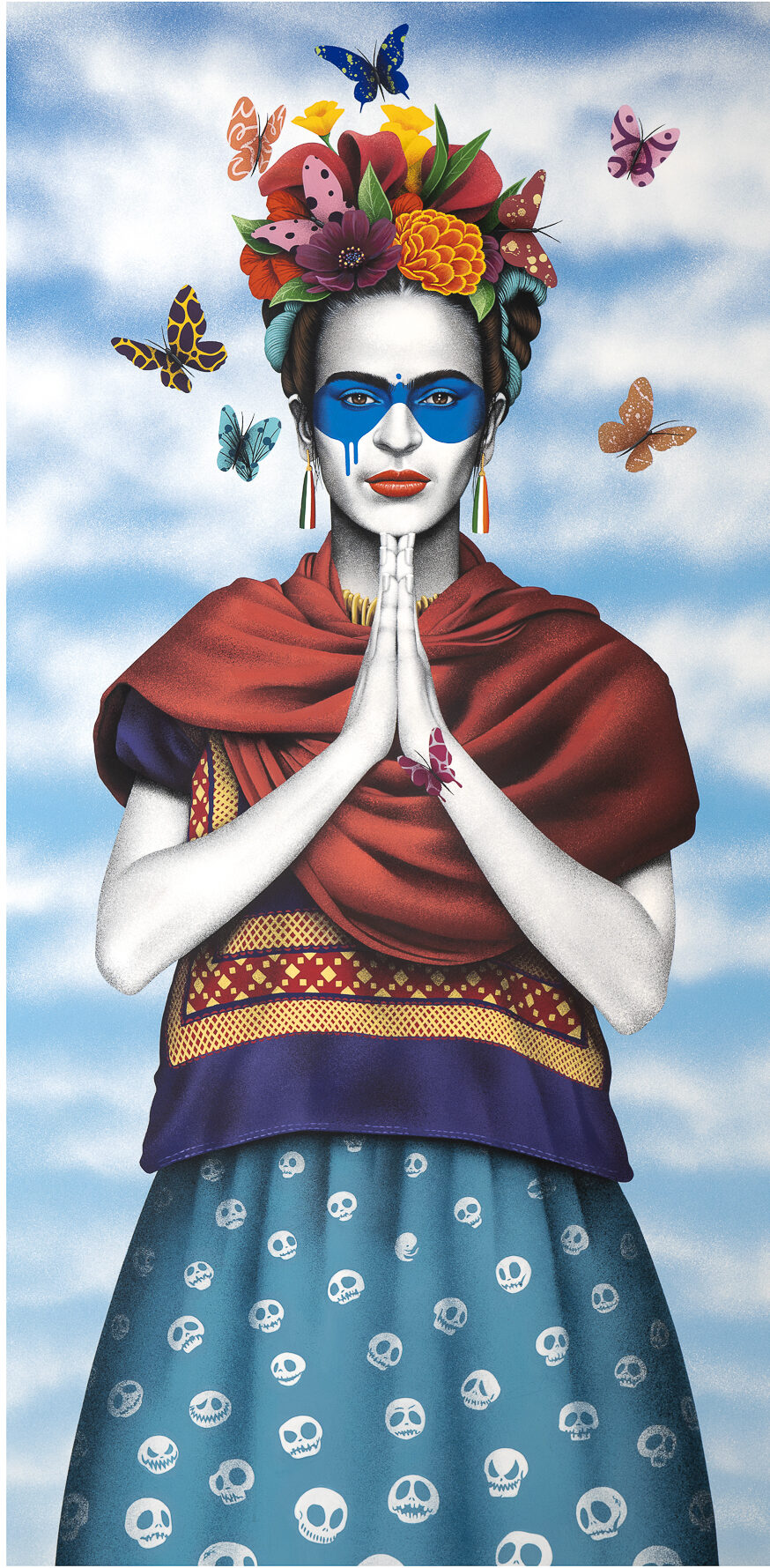

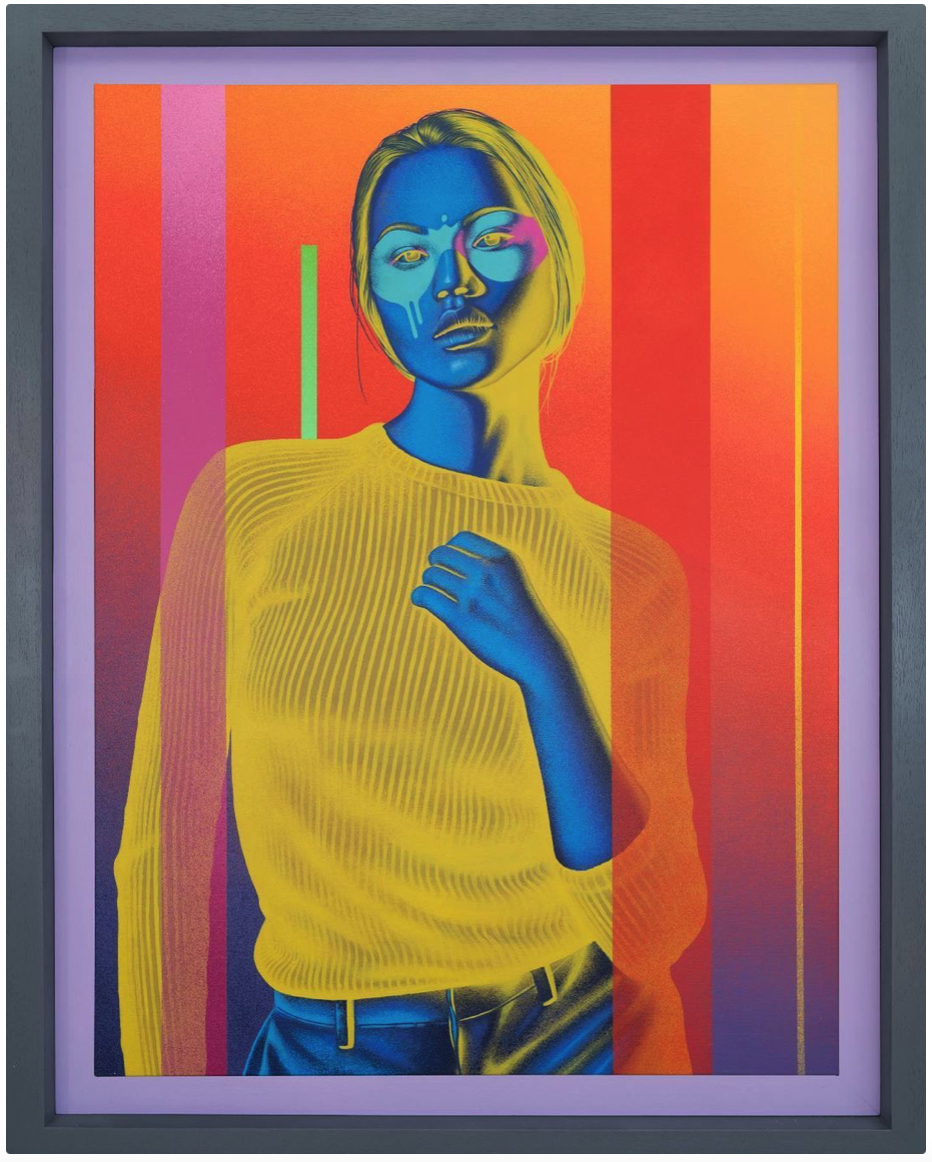

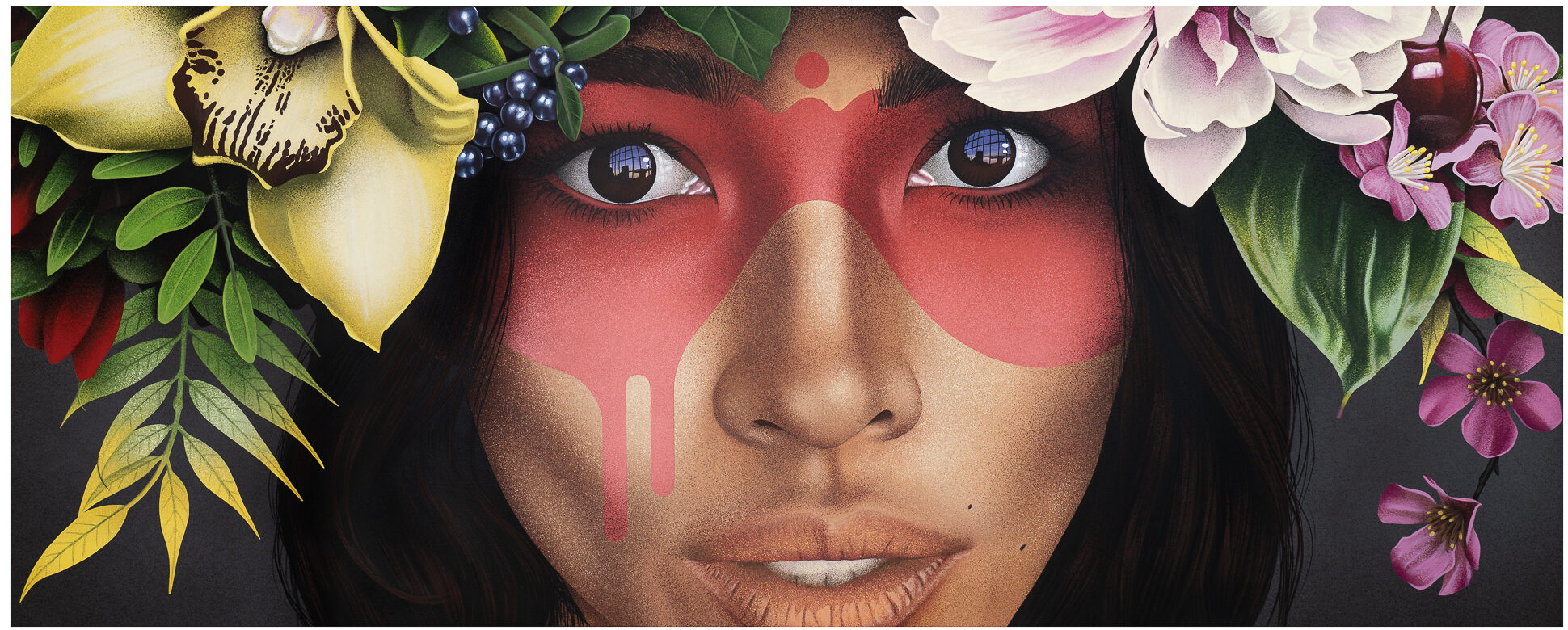

“Urban Aesthetics” the term coined by Irish artist Fin DAC to describe his work, is what resonated when I left his studio after my interview, in Mile End, London. We often take our surroundings for granted, and living in a city, we are privy to the bountiful energy of creativity. Fin’s art resonates with this energy and style. His enigmatic masked women, dressed in extravagant attire, with elaborate hairstyles, hats, or flowers, are an intriguing collaboration of aesthetics. They vibrate with rock chick, punk insouciance, the lavishness of Versailles, the Qing dynasty, Frida Kahlo, Bonaparte, ethnicity, and diversity. The allure is poetic symbolism with cardinal colour palettes portraying womanhood in all her glory. His enormous street murals include magnificent detail, utilising the environment as part of the narrative. His masked women illuminate the urban aesthetic and, for those murals that are often hidden, film footage of their creation often tells an even more intriguing story. Whether viewing his street art in person, or watching videos online, it is hypnotic both in terms of scale and attention to detail.

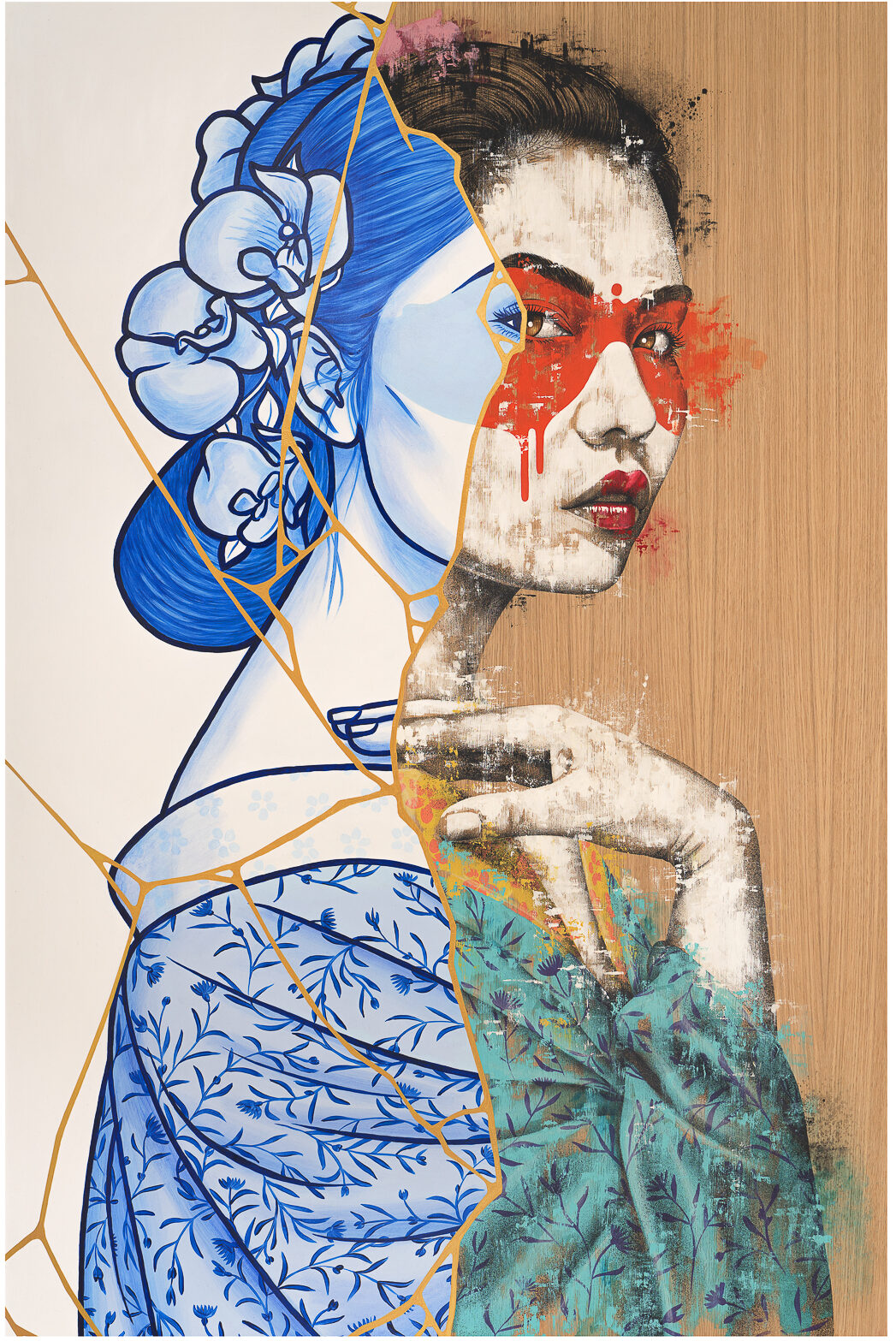

His recent mixed media studio artworks feature a split theme that highlights the duality of a person’s character. They elaborate on the resources of clothing, and made me think of the film The Duchess, with actress Keira Knightley, based on the autobiography of political organiser and activist the duchess of Devonshire. The scene depicts her wedding night. The line goes, “I could never understand why women’s clothes have to be so damn complicated.” The Duchess answers quietly, “It’s our way of expressing ourselves,” she tells her husband “You have so many ways of expressing yourselves, we must make do with our hats and our dresses.” She understood the disparity of power that dominated the lives of men and women at that time. Today, the power of clothes can be a way to decode words, by making statements, an outfit can say what may be impossible or too political to put into words.

Coupled with the narratives of femininity and aesthetic richness, there is an underlying complexity playing with this duality. Fin focuses on depicting primarily Asian women, mostly because of the negative portrayals of them in the media and society in general. “Way too sexualised or too soft, mirroring the typical Hollywood tropes of the fragile ‘Lotus Flower’ or the angry ‘Dragon Lady’. I try to find the midpoint between these two things in my work or paint my characters in a slightly left-of-field manner”. He gives an example, explaining that indigenous women in 18th century Vietnam would never have been allowed to dress in the finery of their French colonisers.

He describes his paintings as portraying fierce, badass women, but not necessarily in the conventional way. When I ask him to explain, Fin states “In today’s world, depicting a badass woman is easy if you make her into a sexual object. Removing that overt sexualisation or objectification is imperative in my work, but it means the allure has to be about more subtle things. That’s where I place the importance. It’s one of the reasons I always say I’m not a painter of female portraits, I am a painter of female characters”.

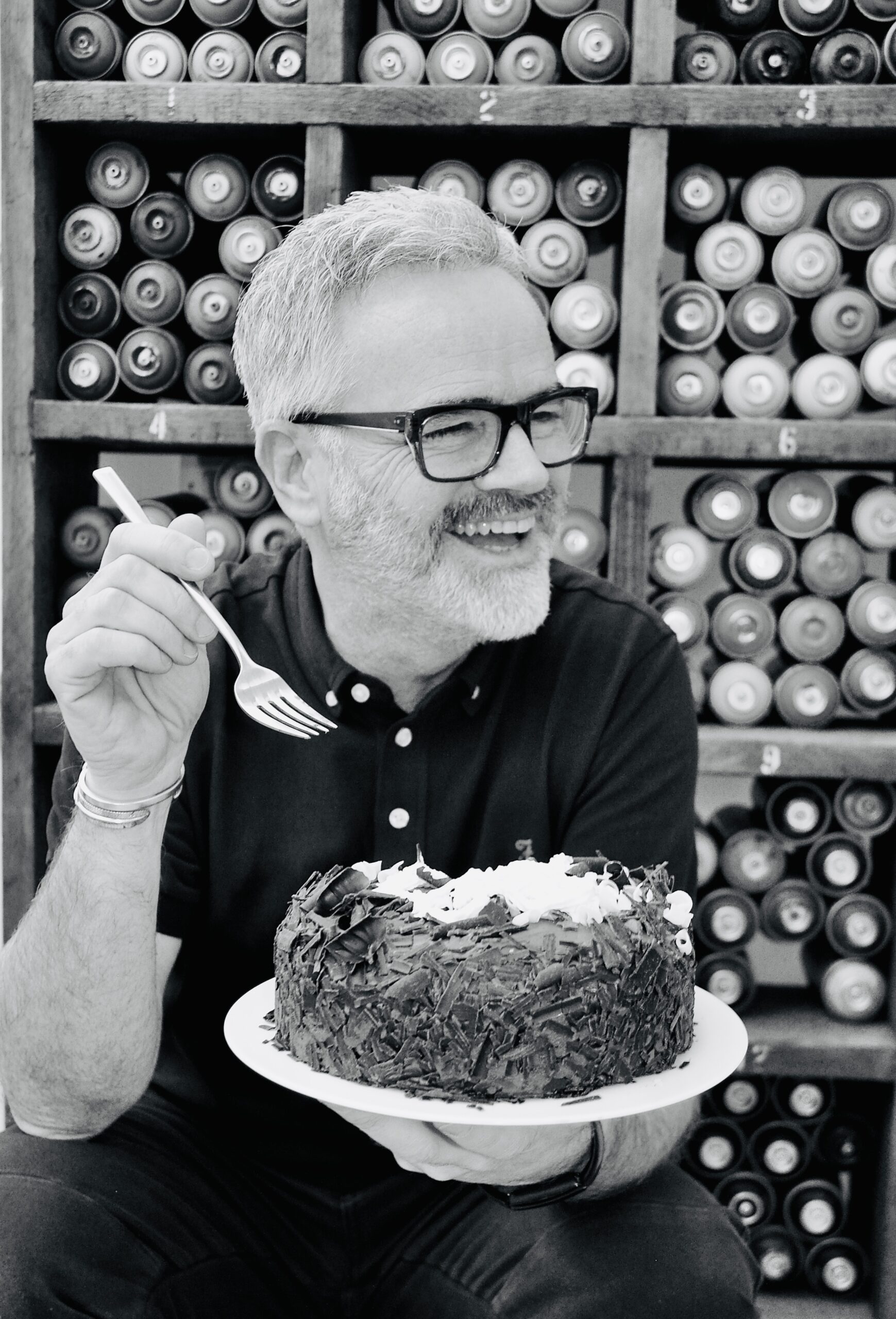

Fin’s journey to become an artist has a hint of nostalgia. His mother recalled that he was somewhat fat and lazy as an infant, and so she gave him crayons and paper to pass the time. It resulted in him being able to draw before he could talk or walk. But his outlook was that everyone could illustrate and that he didn’t see it as any particular gift. Born in Cork, Ireland, his childhood was divided growing up. The first two years were spent with his grandparents in Ireland, then in social housing with his parents in the Elephant and Castle, in what was once described as the worst council estate in London. His father was a painter and decorator, his mother full time raising Fin and his three siblings. However his mother instilled in them, not to be confined or defined by their poor surroundings. They returned to Cork in the mid 70’s and instead of attending art school, Fin followed his older brother into technical college, learning math and technical drawing. Inheriting hand-me-down school clothes that saved money, but massively impacted Fin’s potential to be an artist. Art became simply a hobby.

At 17 he moved back to the UK on his own, living in Uxbridge with an aunt. A well-paid job as an engineering draughtsman for companies like British Rail and London Underground became an adequate substitute for a creative life, and it was supplemented a few evenings a week with DJ’ing gigs during the late 1980s house music boom. In his mid 30’s, he switched careers to work in digital advertising as a web developer. Surrounded by young creative people for the first time in his life, Fin realised immediately that, with or without degrees, no one was any more confident in their creativity than he was. His epiphany was that he had allowed his own fears and worries to stop him from being an artist or following a creative path, and he was determined to change that. Getting into the street art scene and discovering communities of like-minded stencil artists online was a start but it was Banksy’s ‘Can Festival’ in 2008 that really lit the touch paper of his creativity. Seeing the takeover of a tunnel in Waterloo by stencil and street artists from all over the world struck a chord and he knew he wanted to be a part of it.

Alas it wasn’t all plain sailing. Fin initially had negative experiences with the London street art community. “I was a complete outsider and didn’t care for the Boys Club mentality.” But he used this negativity as fuel for his fire and began forging his own path in his own way. “Lots of little breadcrumbs led the way to me becoming a full time artist” he explains. “The initial kick was definitely losing contact with my kids and the associated heartbreak. Painting became my ultimate therapy at that point but the experience proved to me that I could be stronger than I thought I could as well.” Subsequently, an unexpected redundancy a couple of years later, merely proved to him that the universe was pushing him towards a full time art career and that he needed to see the situation as a positive.

With finances in place to cover his new life for one year and with a freedom to travel, he seized the opportunity with both hands and never looked back. He took to travelling to unusual places and painting murals of ever-increasing size and complexity. Murals covering 10 story buildings, rooftops or landmarks as far afield as Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Mexico, Japan, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Tahiti, Hong Kong, France, Spain, Germany, Croatia, Ibiza, Slovakia, Madagascar to name just a few, became the norm.”The murals got more and more attention and that gave me the incentive to carry on” he tells me. His initial modus operandi of complex stencils or projections quickly became unsuitable for the scale of work he was doing. “So learning new techniques, disclosed from other street artists such as Australian artist Rone, was imperative.” The squiggle or doodle method, helps artists with scaling up for very large street art projects, but it all looks very complex when searching tutorials on the method.

Going back to ‘Urban aesthetics’, the Greek word aesthetic, meaning perception, a term coined to ask what makes something beautiful or ugly; from Aristotle’s interpretation, as function and proportion. The Earl of Shaftesbury contended that goodness and beauty were synonymous. Immanuel Kant, tried to analyse beauty and taste, and came to the conclusion that it is in the eye of the beholder, however it opens up a whole new can of worms. The philosophy of art, narratives and judgements of taste, to what makes our pupils dilate when looking at an urban landscape for instance? Street artists have, in recent years, used their skills to make art, changing the mundane into the tremendous.

During the pandemic, Fin shifted from mainly street art and long months on the road, to produce a long-overdue solo exhibition that included artworks derived from all his experiences and embracing lots of new media and techniques. Production took a whole year but, as with his frequent print releases, the show sold out immediately. I asked Fin who inspires him. He mentions the particular impact of Francis Bacon and Aubrey Beardsley, but also adds Ralph Steadman, Alphonse Mucha and Jamie Hewlett as lesser influences.

When I asked him if he could have any painting, he tells me The Climax by Aubrey Beardsley, a print, he recalls, that hung in his parent’s home in his youth. The artwork was part of Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé, the femme fatale kissing the severed head of John the Baptist. “With hindsight, it’s clear to me that Beardsley’s depictions of women had a huge impact on my own vision” he states. When I ask him about what factors make him love an artwork, he explains that he doesn’t know. “Art speaks to me in a subconscious way, and I want to keep it that way; understanding every feeling or reaction we have isn’t a necessity, just being able to experience or feel it is enough.” Fin explains

We discuss the best and worst in the art world, Fin Dac sighs for a second, “The snobbery, ego, and hypocrisy. It should be an open and engaging world but it’s often more about exclusion.” The best he describes “for me is simply the fact that I was able to become an artist and overcome my own negative brainwashing.”

The acronym DAC was founded with a friend from China. It stands for Dragon Armoury Creative and has since become his symbol and trademark. Fin DAC has painted for the 2012 Olympic Games and The Royal Albert Hall, as well as collaborating with brands such as Bang & Olufsen.

Interview: Antoinette Haselhorst

©️ C-A-K-E Contemporary Art Keen Enthusiast Ltd. All rights reserved.

Excerpts permitted with credit and direct link. Full reproduction prohibited.