Richard Berner

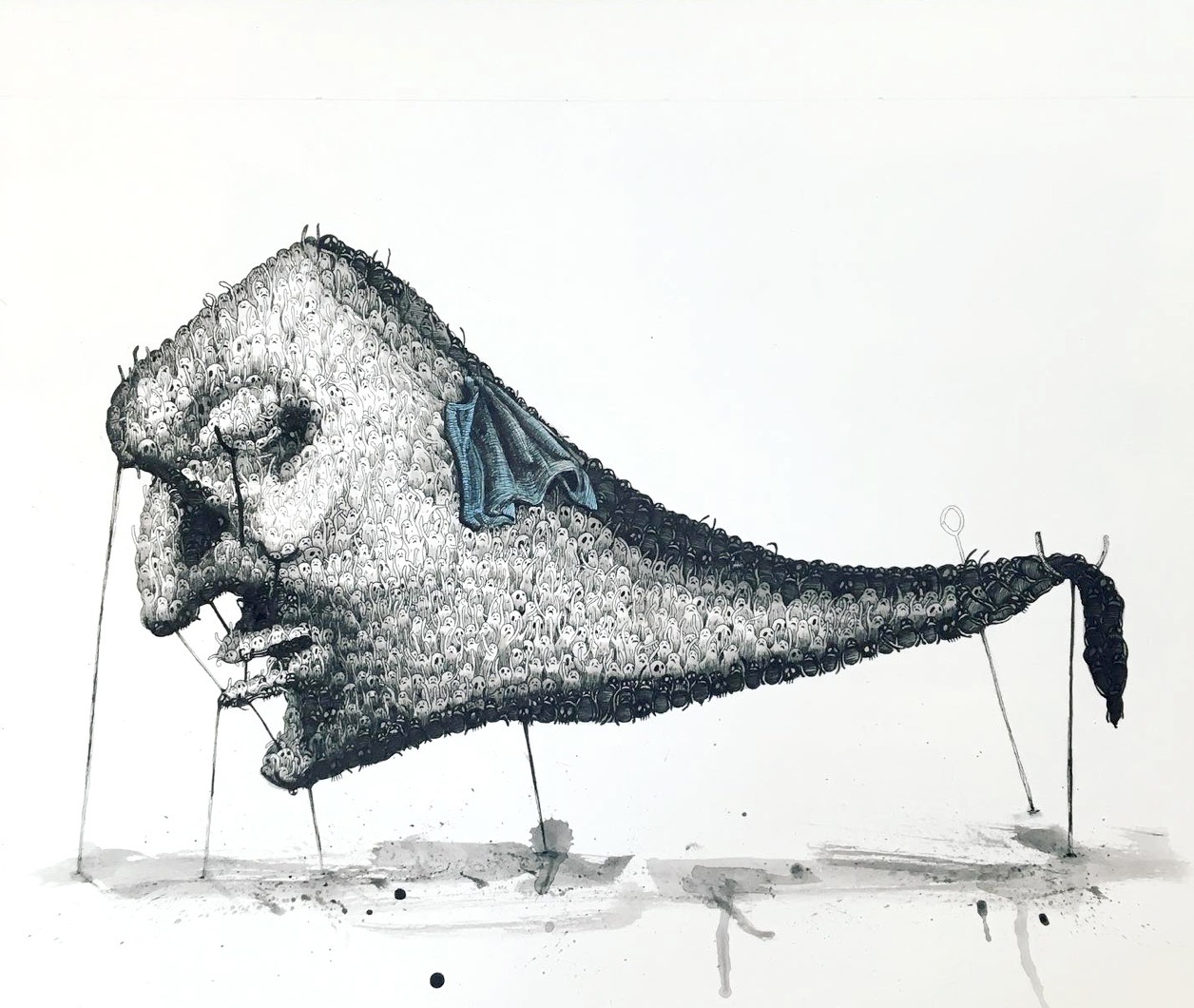

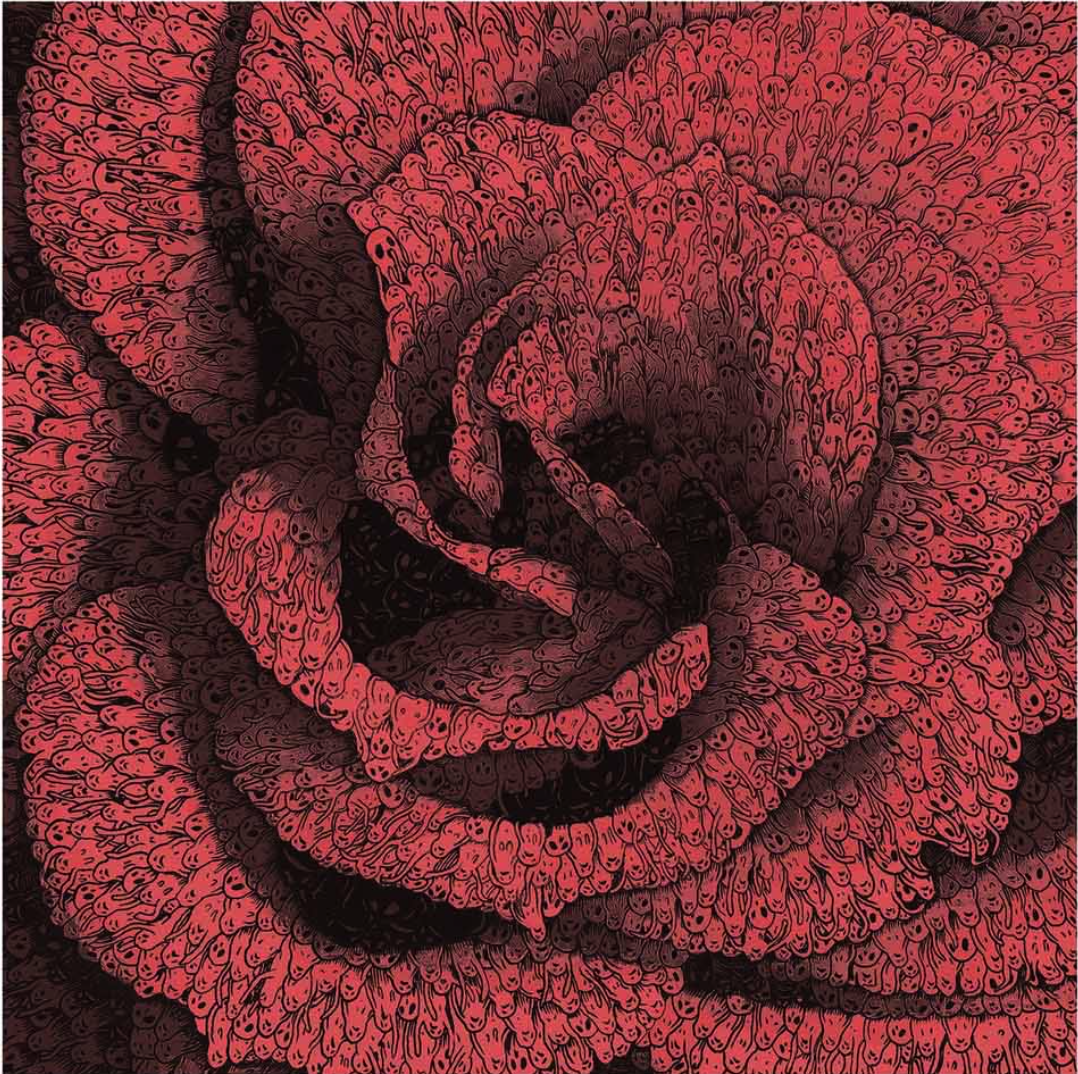

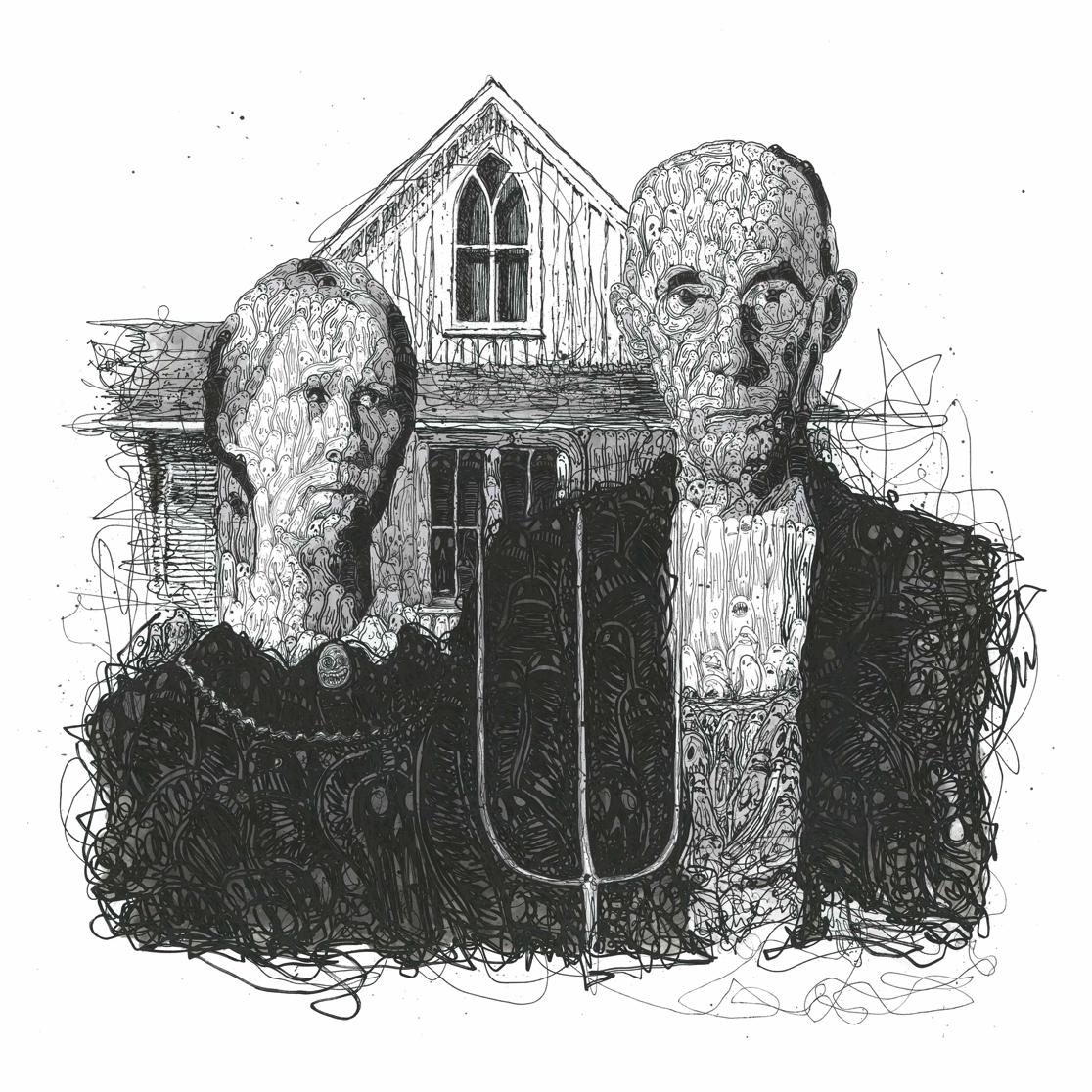

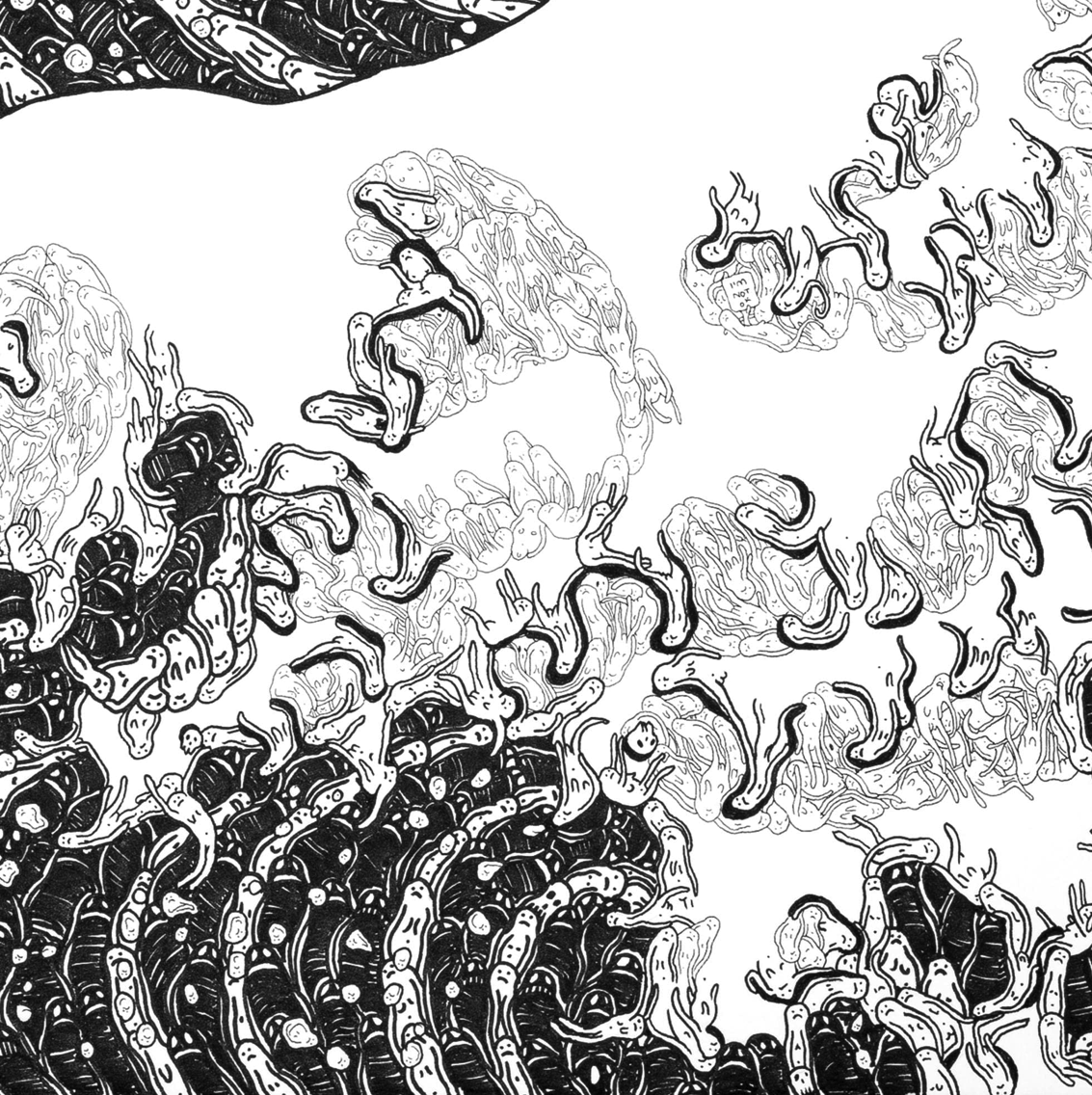

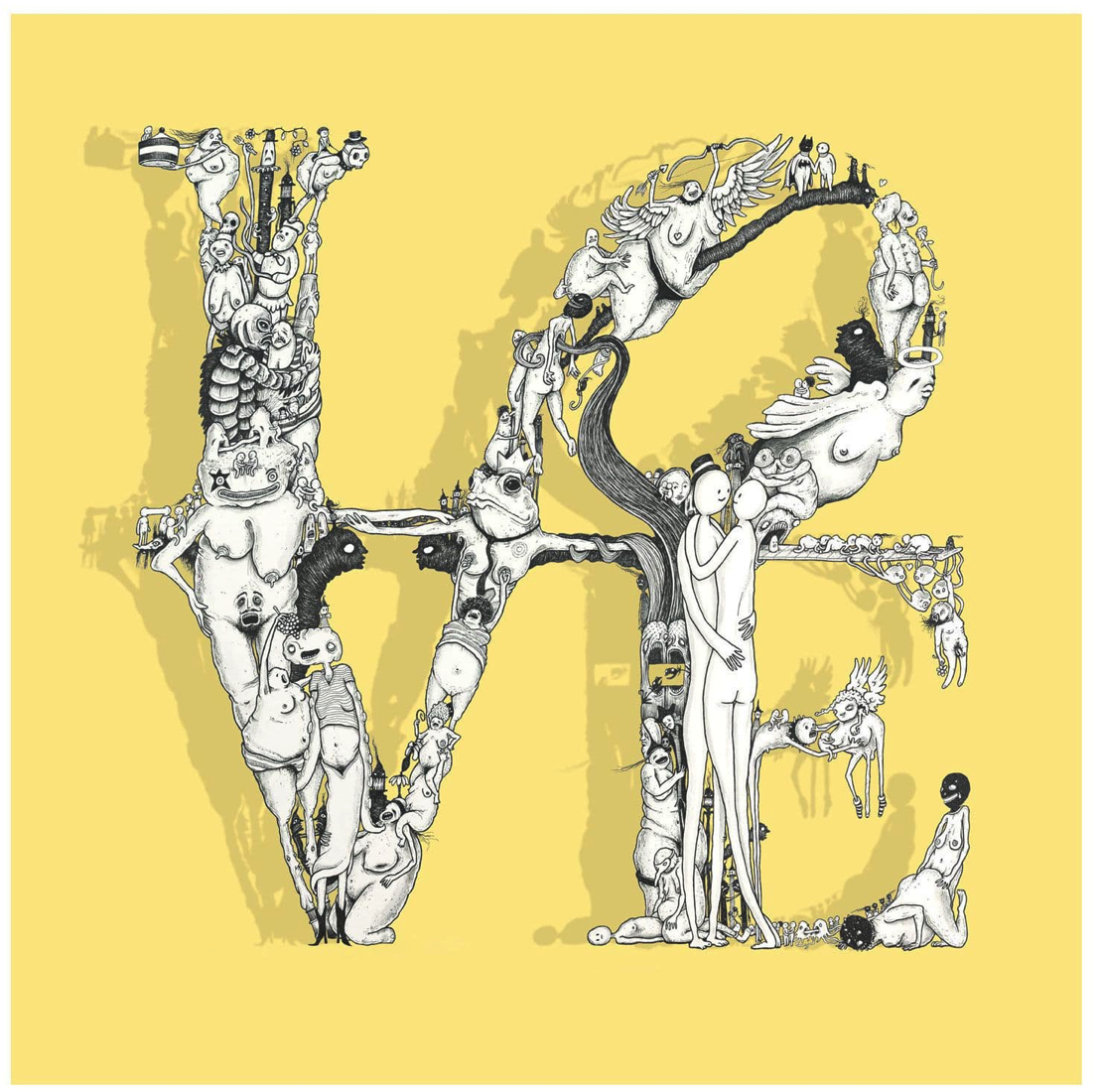

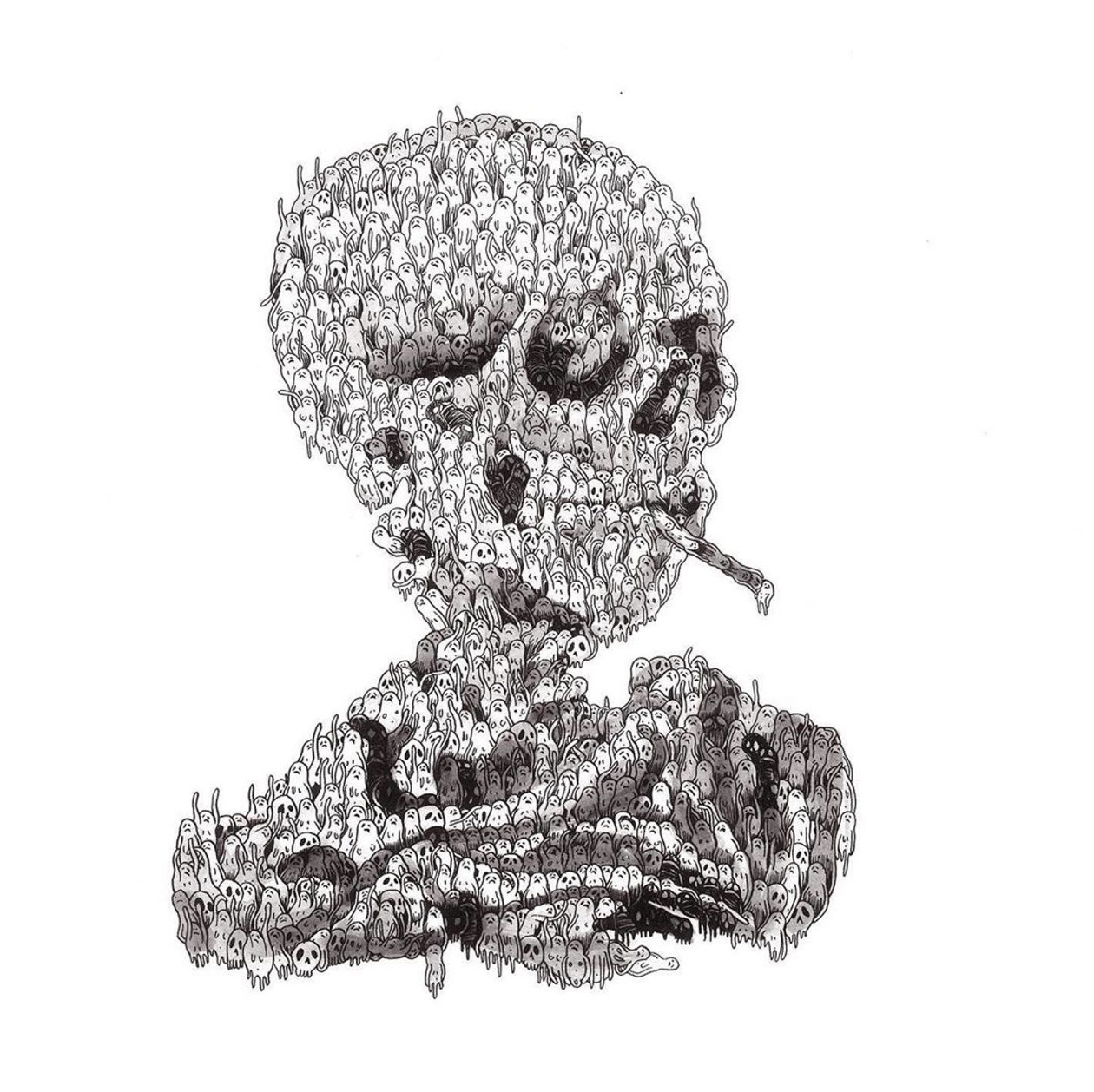

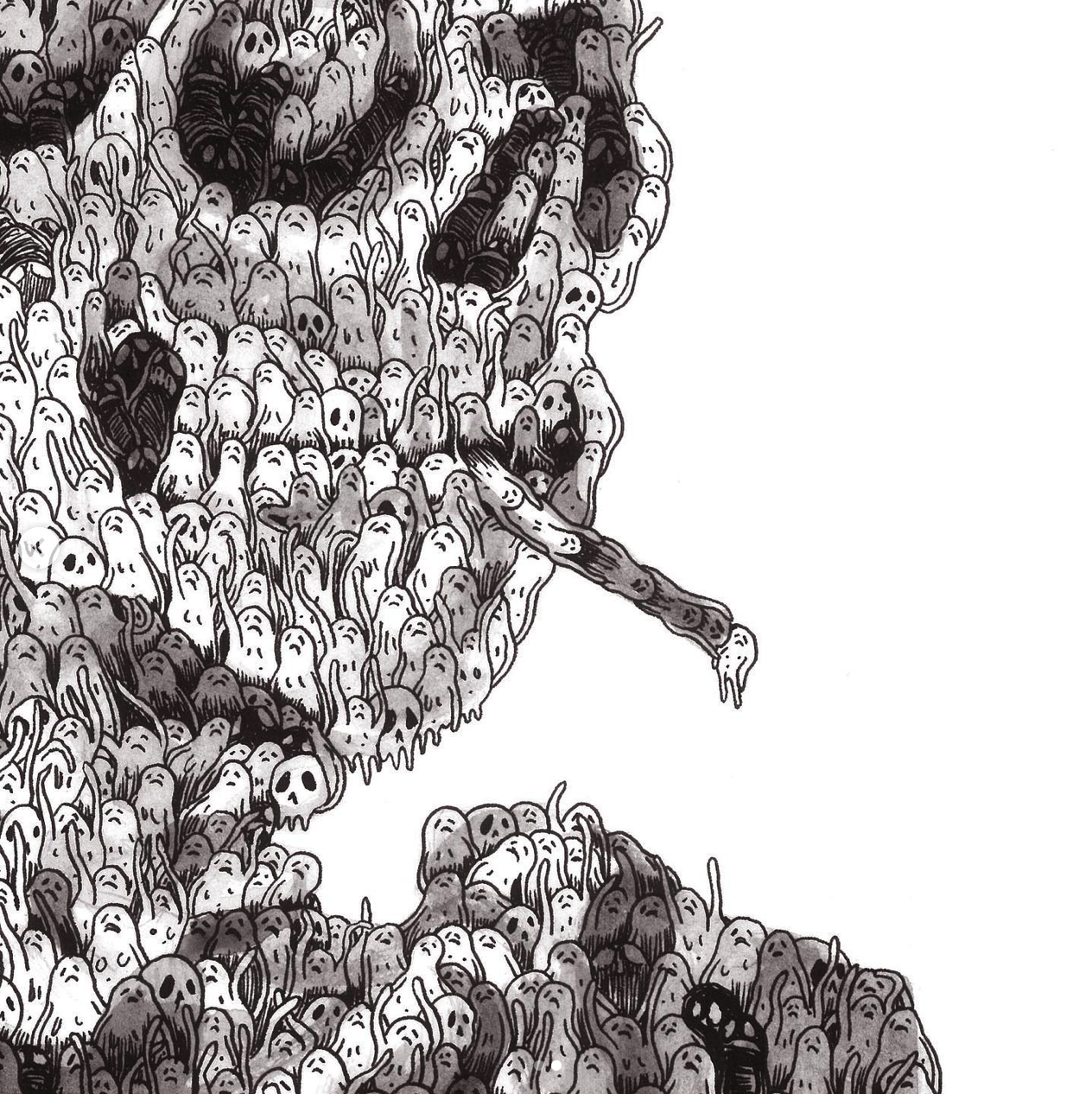

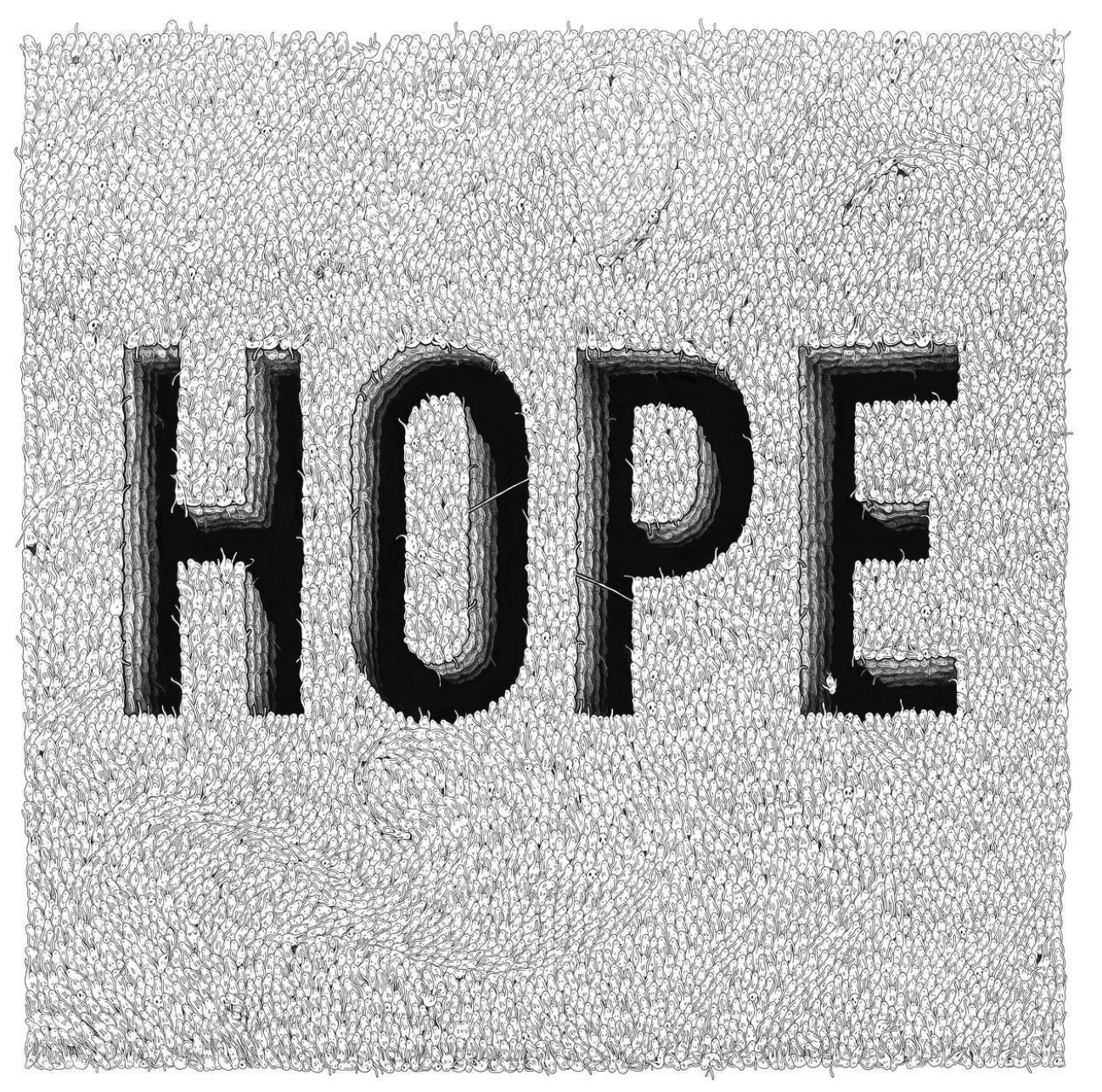

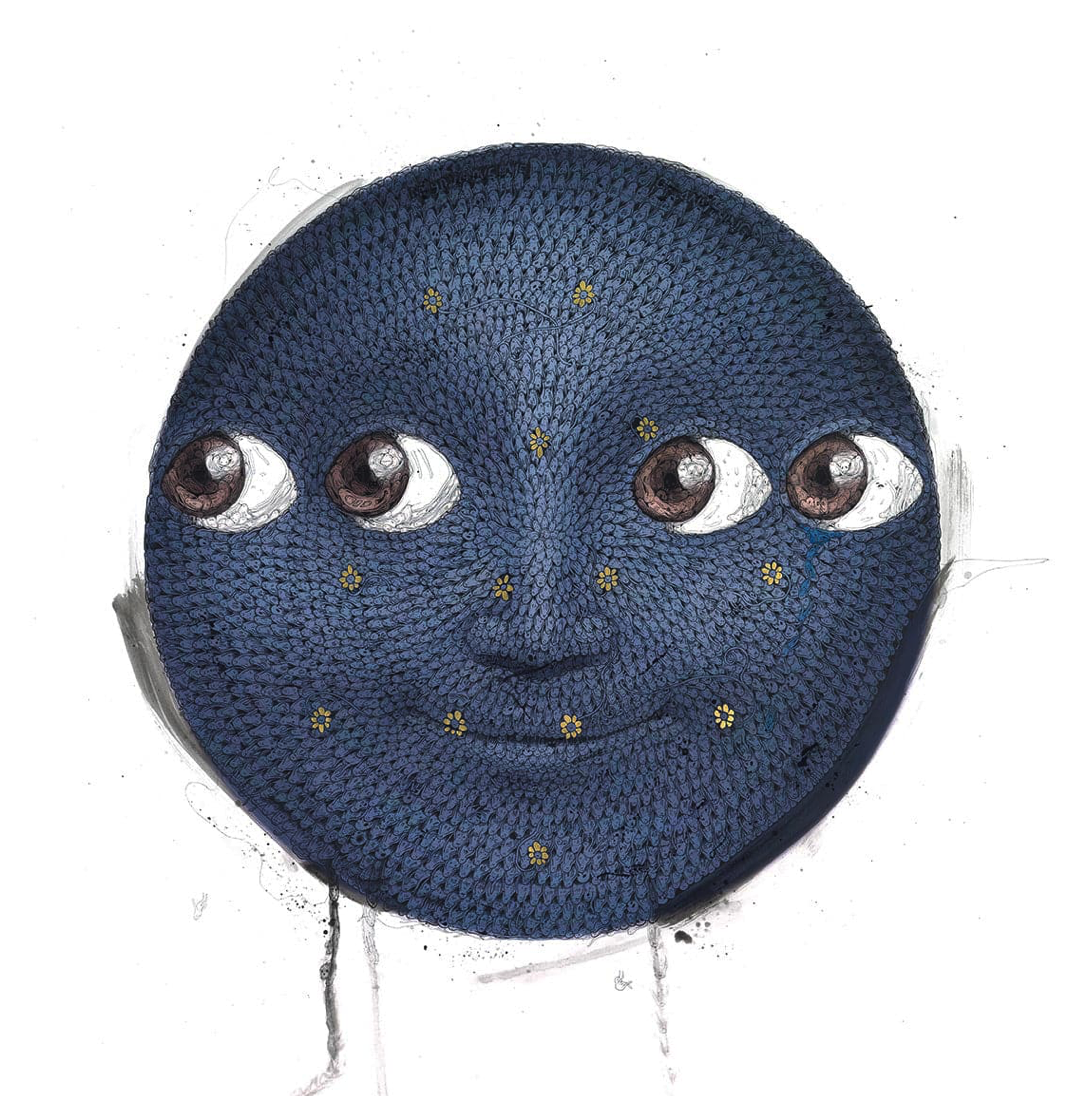

As some of the quintessentially memorable graffiti art from the 80’s started to take centre stage in New York in the Contemporary art world and celebrity culture. In London another form of art culture was centre stage, the advertising agencies at the time creating some of the most outstanding advertising, based on great concepts using iconic humour, that became art in itself, and this led to a large popularity in concept thinking in the UK. Richard, a British artist, stands out with that refined satire, that is so illusively unique. Standing back his artworks look like one thing, an illustration of a skull smoking a cigarette, the Houses of Parliament in London, a bouquet of flowers, or the melting planet dripping, and then you move in closer only to discover a conundrum of allegories, as the artwork reveals a whole new meaning. Within Richard’s artworks there is almost an evolution of the growth from the birth of contemporary art, his artworks are doodles or psychoanalytical little characters that lead one into a labyrinth of questions and metaphors. In the same context there are concepts behind the illustrative images, of thousands of other little drawings.

Richard tells me about art college, he would create these doodle type artworks, and his art teachers would tell him “that’s really not art” and discouraged it, it wasn’t the direction to go, and not really what he should be doing calling it counterproductive to what he should be doing. The whole concept art was the thing, and that’s what they pushed for, Richard tells me. When looking at the timescale it’s interesting to point out how the New York contemporary art scenes were already embracing artist Keith Haring with his animated imagery. If you were to collate Richard’s work to Keith Haring or more recently Sam Cox aka Mr Doodle. Richard’s little’ champs’ as he calls them, are something else altogether, there is an individualism that is more mystifying and at the same time deeply funny, and astute. Maybe there is the existence of the conceptual to his thinking, it’s just that we give names to things. It just explains in a way how the UK was at odds with the contemporary art world of New York at the time and how things have changed.

Richard describes himself as a self taught artist, he did study at art college, “In a way art college put me off art”. His observation, that those who didn’t do well in college, do well as artists. “The classic thing of people saying I wasn’t going to make money from drawings”. He started his doodle drawings when he was a boy at school, and never really stopped, inspired by watching Disney cartoons, and the little characters moving around, and he dreamt of working for Disney when he was little. Born and raised in Middlesex, he attended a College in Twickenham and then art college in Wimbledon, in London. After the course he made the move to study animation in Preston. Richard describes the complexity of animation, and the team work involved. He made his first animated film of an egg rolling around the fallopian tube, admitting that it was somewhat conceptual and surreal.

However, instead of finishing his course, he dropped the visual arts and turned to music as his creative outlet, he did start illustrating again when he created the music posters. Followed by spending a year travelling in Africa, starting in Uganda and journeying down through Kenya and Tanzania, then through China, Fiji and Mexico before returning home to Middlesex. In 2014 his life changed, a friend had a spare room to rent in Brighton. Inspired by all the artists and creativity in the area, he started to draw again. “Art is like an energy, it kind of flows through, when there is not a strict meaning of things” Richard explains. His first couple of pieces were of Brighton landmarks, with what he describes as interesting characters, embodying the structure of the artwork. He recounts starting to draw and then just going into the zone and into his own space. The narratives are not intentional, Richard explains, “I am not sure, sometimes there is and sometimes it just happens as I go along”. He describes how he stumbles upon things that work, “That tad of surrealism” inspired by Dali, or Swiss artist Hans Rudi Giger (H.D.Giger) the creative brains behind the visual direction of the film “Alien” and graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher (M.C.Escher). Other influences are street artists and pop art, he tells me, describing how images just emerge, as he likes to work organically, it’s the hand on paper and the feel of the ink.

Friends started trying to sell his art, a contemporary art gallery Art Republic, now Enter Gallery offered to buy prints of his artwork. It was a situation where Richard had to borrow money from a friend to afford the printing costs. It paid off from an initial print run of 10 artworks, to now over a 100k followers on Instagram and his collectors buying his art and prints from him all over the world, that he now makes a living as an artist. The shape of his work evolved at the Roy’s art fair, Richard describes selling his prints of London buildings, however it was the illustrations of old telephone boxes with his little characters hidden in them, that caught the curiosity of the crowd. Each telephone box is slightly different, and his experimentation with 3D. It evolved from there at first quite a lot of rejections, “To just making something that nobody can ignore” he tells me. His large scale moth artwork created a bit of a buzz, he explains as he smiles humbly.

Currently he is working on something a bit different, a series of adapted vintage paintings. His ambitions to take his work and exhibit abroad, he expresses his greatest achievement to date, his first solo show ‘Move in Closer’ at The Old Bank Vault Gallery in London, and all his work sold out. He describes perfection as all the little miracles that make an artwork special. However what is really behind his work or what he wants to convey, that is up to the viewer, although he does give away the juxtaposition of the humour, sadness and pain. It’s an intrinsic feeling an artwork gives him, that makes him love it.

Interview: Antoinette Haselhorst

©️ C-A-K-E Contemporary Art Keen Enthusiast Ltd. All rights reserved.

Excerpts permitted with credit and direct link. Full reproduction prohibited.